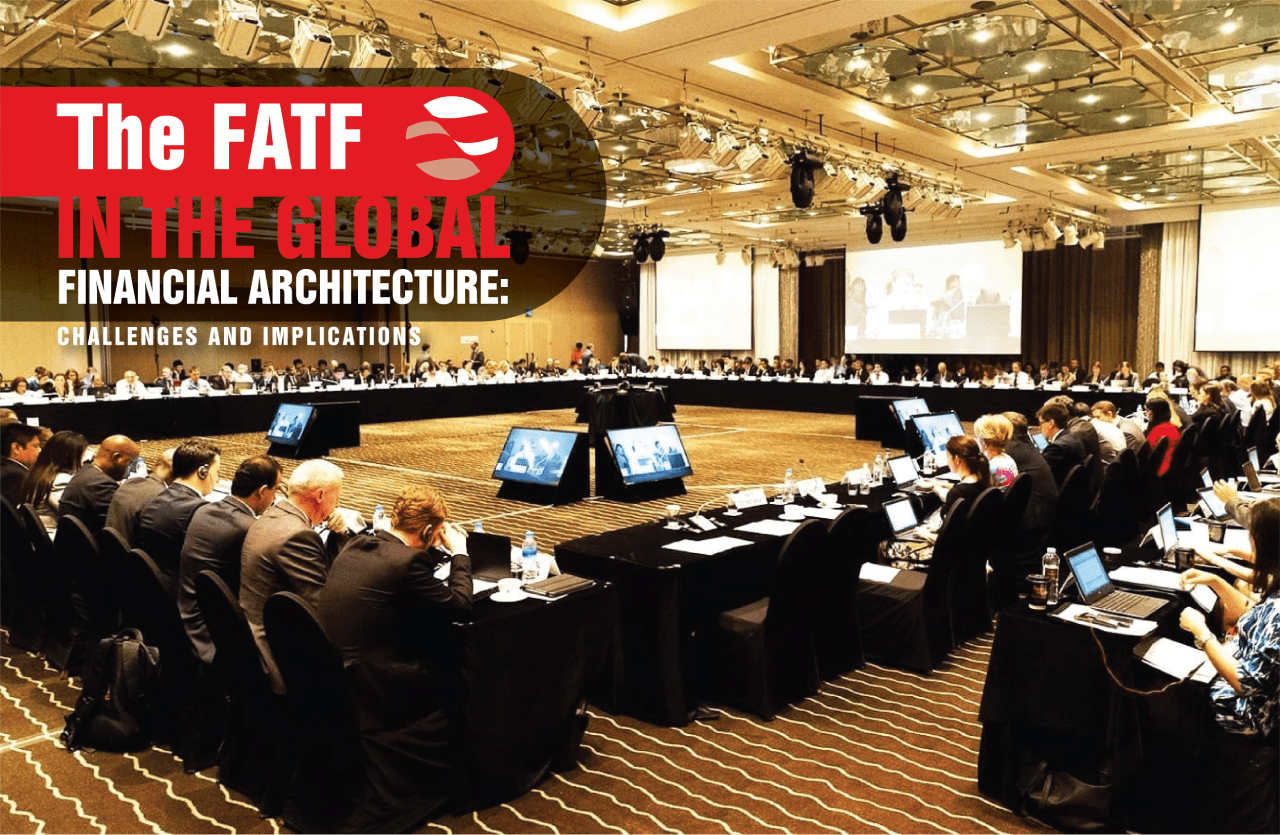

There are various structural problems that underpin the FATF as it stands today, and they are important enough to evoke wider public attention as well as the specific notice of key Pakistani stakeholders. Although the FATF is situated in the field of finance, it is more appropriately deemed a political organization, because a sizeable political undercurrent permeates its working and structure. There are six important structural characteristics of the FATF that are discussed as follows:

The first overall question is that of legitimacy. It should be noted that the FATF is not a UN-body or pillar of international institutional arrangements as many stakeholders may think. It is just an inter-ministerial body with the purpose of setting financial standards. The second question is that of its membership, which is voluntary and largely comprised of EU member states; and the FATF’s membership is not mandated by a multilateral institutional body.

A third question is that of its regulatory behavior, which has been carried out in the largely ad-hoc manner. Because new rules are abruptly added to its mandate, even a country that may have been previously compliant (as Pakistan was) can come into its crosshairs at any time. This is another troublesome aspect of the FATF, because its machinery can be subverted to add new recommendations at any time (particularly at its plenaries every trimester) to suit the interests of its key member states. As a fourth point, FATF does not have an accountability mechanism whereby it can report its oversight functions or give countries recourse against its decisions. While Pakistan is reporting its measures to the FATF, the task force itself is very opaque and lacks considerable transparency.

A fifth and crucial point is that the FATF does not enjoy universal acceptance, and even OECD countries such as the United States (specifically, the US Treasury Department) have categorically stated that they do not expect their institutions or territories (such as American Samoa) to adhere to the EU-led standards that dominate the FATF. Therefore, the recommendations towards “high-risk and non-cooperative jurisdictions” are certainly not binding.

Perhaps most troubling of all, India has assumed co-chairmanship of the FATF’s Asia-Pacific region, which poses a serious security risk as it allows India to help dictate the sanctions imposed. Recent irresponsible and inaccurate comments by their Defense Minister, Rajnath Singh, suggested that Pakistan “could be blacklisted at any time.” While not true, it does reveal how India schemes to weaponize the FATF. Pakistan’s response should be broader and more forceful in highlighting this risk of Indian subversion.

Yet these should not be seen as reasons to reject the FATF’s ostensible message of financial regulation per se. However, the fact that these issues underpin the workings of the FATF is cause for immediate as well as long-term concern. The aforementioned discussion should point to three conclusions:

- Its stipulated requirements change arbitrarily and abruptly

- The FATF’s own legitimacy has yet not been fully established

- Its attitude towards Pakistan reflects the “do-more” rhetorical strategy that the United States has repeatedly employed against Pakistan to mask the shortcomings of others

The fact that India should be using the FATF is incredible given its own horrific record of dark money and shadowy transactions. According to the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA), India’s shadow economy amounts to 17.22% of GDP, which would equate to 516 billion dollars. In other words, India’s shadow economy alone is larger than the entire economy of the UAE, Malaysia, or Denmark. India’s shoddy and sweeping attempts to supposedly counter their black economy have included PM Modi’s demonetization campaign, which a consensus of economists and the Reserve Bank of India alike have deemed a failure, not just in hurting economic growth, but also in growing the number of illicit transactions (particularly counterfeit currency to replace the demonetization) by an alarming 480%. With so much dark money slushing around, including for illicit activities and terrorist initiatives, the idea of India taking the chair is absurd.

Taking a step back, we must recognize that, if the powers-that-be truly cared about international money laundering and “dark money,” they would most certainly be waging a war against the Cayman Islands, the Bahamas, Vanuatu, Guernsey, Gibraltar, the British Virgin Islands, and Delaware. The FATF has existed since 1989, circa the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, and since then the amount of dark money slushing around the world has exploded in absolute terms as well as relative to the total global money supply. But the greatest centers of non-transparent financial gimmickry and suspect acts are not in Third World nations. They are in fact right at the heart of Western capitalism: in locations such as London, Frankfurt, New York, and Delaware.

In fact, Pakistan has already long imposed strong anti-terror financing laws that are tougher than those stipulated by the FATF, but their implementation has been haphazard and characterized by a reactive stance: whenever India beats the drums on Pakistan’s supposed “terror funding”. Pakistan has responded by implementing some financial oversight and actions. Pakistan’s approach must shift from the reactive to the proactive. The pursuit of better financial regulation and oversight is in Pakistan’s inherent interest, and should be seen as part of a series of reforms to be taken to spur more sustainable economic growth in Pakistan over the long-run. Pakistan has always struggled with the problem of a large shadow economy, and erasing that shadow is of supreme national interest, in order to: normalize economic activity, draw tax revenues from it, and have a better grasp of what is occurring within the country.

What is then of pressing concern is noting how being blacklisted by the FATF could impact the lived experience of Pakistanis today.

Implications of the FATF “Black-List”

Despite its questionable legitimacy, partisan behavior, and subjective modus operandi, the FATF could have a significant impact on economic life in Pakistan in both the immediate and long-term. Indeed, there are several important ways in which the FATF can leave a severe dent in Pakistan’s economic growth trajectory, as listed below.

The first economic aspect to be affected would be remittance flows, which are the life-blood of the Pakistani economy. The FATF’s blacklisting can stifle this essential avenue of foreign exchange that helps to keep the country afloat. A second economic problem that blacklisting would create is in Pakistan’s negotiation with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for an interim lending arrangement to shore up its finances. A third economic problem lies in the inflows of FDI into Pakistan, which have already been falling in the calendar year 2019 despite earlier rises due to CPEC. A fourth problem is that Pakistani banking institutions will come under heavier scrutiny, and may be made the subject of investigations.

A fifth problem pertains to the function of philanthropic organizations (charities), since FATF black-listing would mean that a broad swathe of philanthropic organizations would face legal difficulties (registration etc.), raising funds, and disbursing their proceeds through legal channels, and this would have very socially unequal (anti-poor) consequences for the country.

A sixth problem is that Pakistani individuals will face even harsher barriers when engaging in overseas transactions. A seventh problem is that domestic inflation will rise due to a reduction in cross-border and international financial transactions caused by higher restrictions. In the calendar year 2019, it has been observed that inflation is rising considerably and the purchasing power of the common man has declined significantly. FATF blacklisting would make this even worse. When taken together, it should be evident that the FATF’s blacklisting risk is severe by any measure, and also that the FATF represents an instrument of economic violence against Pakistan.

Countries seeking to weaken Pakistan need not spark a military confrontation, when the FATF can do their dirty work just as viciously. While 2019 has demonstrated that Pakistanis have both the will and the means to defend their country against overt violence (such as in the tensions with India during February-March), the subliminal violence of an economic noose still hangs over the country’s head, and the FATF is an adversary in that battlefield of bank balances.

Conclusion

Pakistan cannot ignore the FATF. It is a member of that task force, and it is evident that withdrawal from the FATF would send a terrible signal to the international community. Whether Pakistan should have joined the FATF in the first place is another matter altogether. In hindsight, perhaps it shouldn’t have. At the same time, the principle of fighting terrorist financing and anti-money laundering, or even at a broader level: of closing the shadow economy, is laudable, and one that Pakistan must pursue in any case, at its own behest.

While several governments have made partial approaches towards solving this problem, resource constraints have been immense in a country where the vast majority of people point their finger at the government and yet do not pay any tax to bolster it. The lackadaisical attitude towards undocumented, shadowed economic life amongst a largely illiterate population cannot persist in the 21st century, and since Pakistanis have not managed to address this problem themselves, the world (for its own good) is solving that problem for Pakistan, by choking it off.

Pakistan must now manoeuvre adeptly to appease the international community so as to remain a part of it. The following are a brief set of recommendations in that regard.

- Public awareness on the impact of informal economy: The public should recognize that its constant anti-tax attitude and lax tolerance for the shadow economy is the basis for the current challenges that beset the country.

- From proactive to reactive: Pakistan should not wait for the United States or India to raise a hue-and-cry about terrorist financing or money-laundering in the country, and then take reactive piecemeal measures. Instead, a comprehensive effort to translate the measures highlighted by the FATF (and even more so by national legislation) should be undertaken. Economic exclusion is a priority-worry for the country, and current limited resources assigned to this effort are unjustifiably low.

- Signaling its commitment: Taking steps to implement our own national laws must be undertaken immediately, as this will signal our commitment to the international community that we wish to remain a part of it and respect the need for closing the shadow economy and curtailing illicit financing. Those steps need not be specified here because they are categorically stated in our relevant national laws.

- Greater pressure on the FATF stakeholders: Writing formal letters does not seem to be a sufficient means of persuading our economic adversaries. A concerted effort to lay pressure, through diplomatic channels, through the media, and through high office must be engaged with. But above all, our primary institutions dealing with these issues must engage in a tougher pressure-strategy, as well as a public relations effort, to show the activities they are undertaking –this applies most to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP).

- Capacity building of our team: Our engagement with the FATF is by nature one of negotiation, which is why Pakistan requires strong negotiation team(s) to present the country’s case effectively. The teams working on the FATF must therefore comprise highly qualified and trained experts, and special training should be given to them to prepare for the challenge ahead.

A concerted national effort must be undertaken to grapple with both the economic violence as perpetrated by the larger stakeholders of the FATF, as well as the bigger problem of a haphazard approach that Pakistanis have taken towards addressing the ramshackle nature of an informal economy.