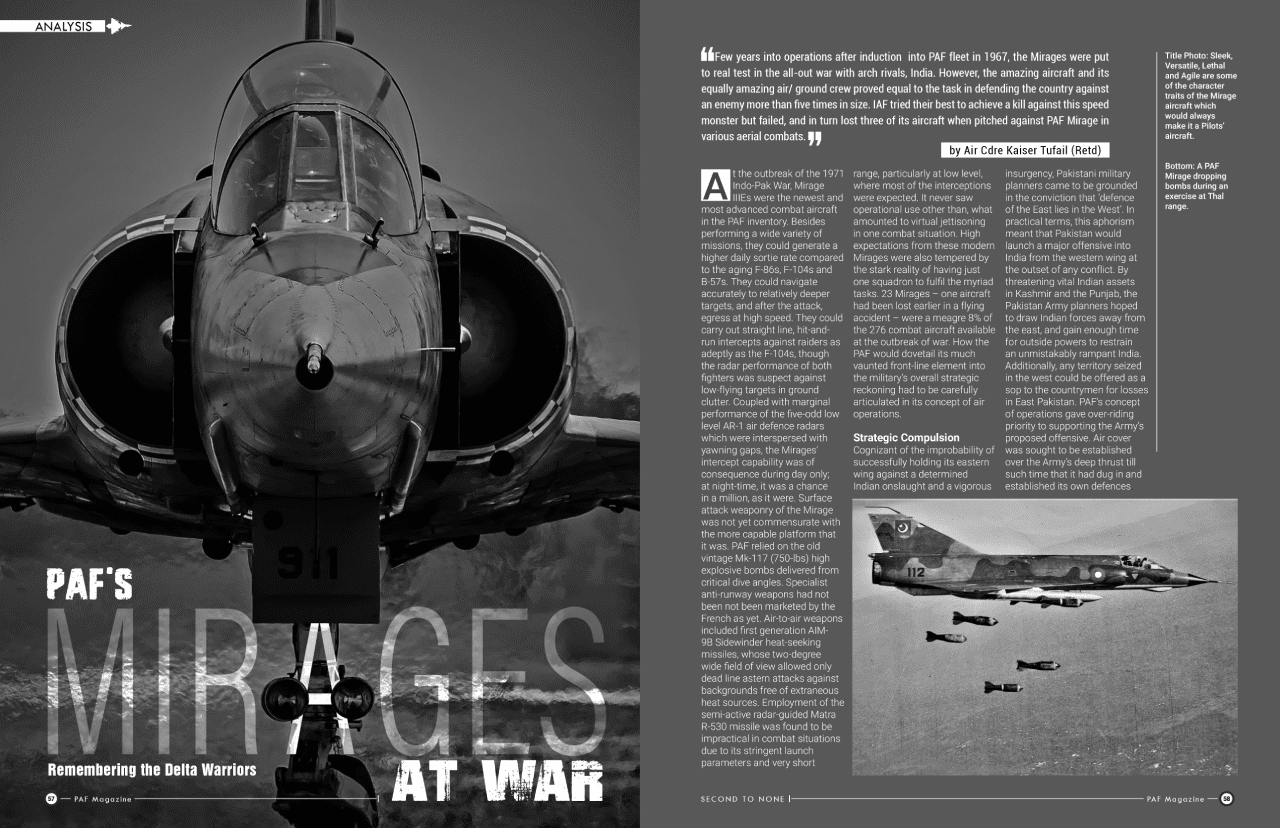

Remembering the Delta Warriors

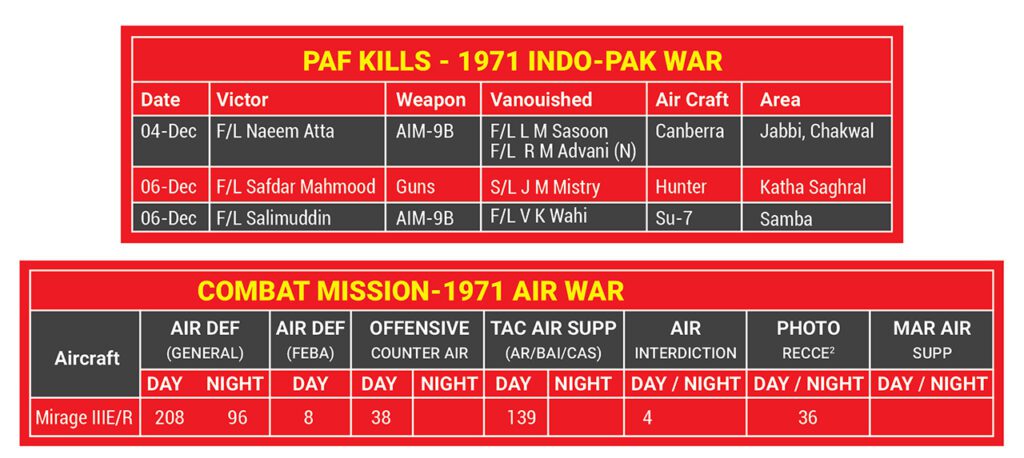

Few years into operations after induction into PAF fleet in 1967, the Mirages were put to real test in the all-out war with arch rivals, India. However, the amazing aircraft and its equally amazing air/ ground crew proved equal to the task in defending the country against an enemy more than five times in size. IAF tried their best to achieve a kill against this speed monster but failed, and in turn lost three of its aircraft when pitched against PAF Mirage in various aerial combats.

At the outbreak of the 1971 Indo-Pak War, Mirage IIIEs were the newest and most advanced combat aircraft in the PAF inventory. Besides performing a wide variety of missions, they could generate a higher daily sortie rate compared to the aging F-86s, F-104s and B-57s. They could navigate accurately to relatively deeper targets, and after the attack, egress at high speed. They could carry out straight line, hit-and-run intercepts against raiders as adeptly as the F-104s, though the radar performance of both fighters was suspect against low-flying targets in ground clutter. Coupled with marginal performance of the five-odd low level AR-1 air defence radars which were interspersed with yawning gaps, the Mirages’ intercept capability was of consequence during day only; at night-time, it was a chance in a million, as it were. Surface attack weaponry of the Mirage was not yet commensurate with the more capable platform that it was. PAF relied on the old vintage Mk-117 (750-lbs) high explosive bombs delivered from critical dive angles. Specialist anti-runway weapons had not been not been marketed by the French as yet. Air-to-air weapons included first generation AIM-9B Sidewinder heat-seeking missiles, whose two-degree wide field of view allowed only dead line astern attacks against backgrounds free of extraneous heat sources. Employment of the semi-active radar-guided Matra R-530 missile was found to be impractical in combat situations due to its stringent launch parameters and very short range, particularly at low level, where most of the interceptions were expected. It never saw operational use other than, what amounted to virtual jettisoning in one combat situation. High expectations from these modern Mirages were also tempered by the stark reality of having just one squadron to fulfil the myriad tasks. 23 Mirages – one aircraft had been lost earlier in a flying accident – were a meagre 8% of the 276 combat aircraft available at the outbreak of war. How the PAF would dovetail its much vaunted front-line element into the military’s overall strategic reckoning had to be carefully articulated in its concept of air operations.

Strategic Compulsion

Cognizant of the improbability of successfully holding its eastern wing against a determined Indian onslaught and a vigorous insurgency, Pakistani military planners came to be grounded in the conviction that ‘defence of the East lies in the West’. In practical terms, this aphorism meant that Pakistan would launch a major offensive into India from the western wing at the outset of any conflict. By threatening vital Indian assets in Kashmir and the Punjab, the Pakistan Army planners hoped to draw Indian forces away from the east, and gain enough time for outside powers to restrain an unmistakably rampant India. Additionally, any territory seized in the west could be offered as a sop to the countrymen for losses in East Pakistan. PAF’s concept of operations gave over-riding priority to supporting the Army’s proposed offensive. Air cover was sought to be established over the Army’s deep thrust till such time that it had dug in and established its own defences. It was also felt necessary to attack 4-5 Indian airfields that directly threatened the offensive once it was underway. To prevent timely arrival of logistic reinforcements, PAF was to interdict supplies directly serving the Indian forces; this meant attacking rail yards and other supply nodes soon after start of the offensive. Until the army’s offensive was launched, limited close air support during holding operations was to be provided. Tactical recce was to be conducted regularly to determine the changing disposition of enemy formations. Finally, PAF was to maintain pressure on the IAF with sustained disruptive strikes against some of its forward and rear bases, to accrue a measure of psychological ascendancy in the conduct of air operations. From PAF’s standpoint, it was easy to see that the modern Mirages were the weapon of choice for operations during the critical land battle planned for the western theatre. Yet, far from singling out these vital assets for the critical stage of the war only, it was boldly decided to employ them to the hilt in all phases. The bulk of No 5 Squadron was deployed at its parent Base, Sargodha, under command of Wg Cdr Hakimullah, formerly an old hand on the F-104s. A detachment of six aircraft, led by Sqn Ldr Farooq F Khan, was moved to the deeper located satellite Base of Mianwali to provide redundancy in the night intercept role, and also as a back-up strike element for the all-important land offensive. Mirages were thus poised to be at the forefront of PAF’s ‘coup de main’.

Softening Up

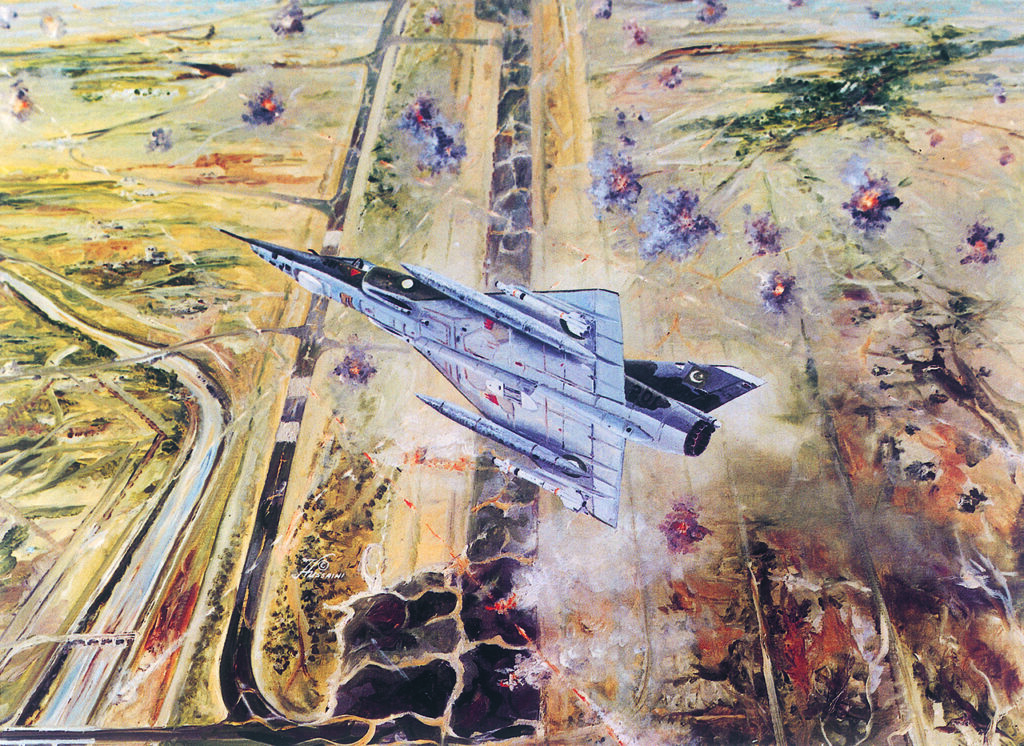

Contrary to the general perception, PAF’s dusk strikes of 3 December against some of the forward Indian airfields were not pre-emptory at all, as the Indian invasion of East Pakistan had already taken place in earnest, on 21 November. While these strikes were, of course, aimed at cratering runways and destroying radars, they also had an intrinsic ‘provocative’ element which the PAF planned to cleverly exploit through its well-prepared air defences, when IAF retaliated the following morning. Mirages got a small share of 8 airfield strike sorties in the opening round of the counter-air operations campaign that also included 24 airfield strikes by F-86s and 4 radar strikes by F-104s. Wg Cdr Hakimullah led a flight of 4 Mirages to Amritsar, while his flight commander, Sqn Ldr Aftab Alam, led another flight of 4 Mirages to Pathankot. Heading east into fast-fading light, Wg Cdr Hakimullah was able to take a cue from Amritsar runway lights, which were inexplicably glimmering when it should have been a complete black-out. His formation pulled up for a dive attack to deliver two 750-lb bombs each. Except for No 4, whose bombs did not release due to some malfunction, the rest were able to put in the attacks in the beginning of the runway. Sqn Ldr Aftab Alam’s formation did not have the good fortune of catching Pathankot with its lights on, and could not execute a proper attack in the evening haze and low light. The bombs fell in the general vicinity of the airfield. Given the very short distance from the border, IAF was unable to scramble interceptors from the ground, so standing patrols should have been a sensible option. With no interceptors, all raiding aircraft came back unscathed. The disruptive raids were continued into the night by the B-57s.

The missed strike at Pathankot was repeated by Sqn Ldr Aftab Alam’s formation the next afternoon. This time, all the bombs found their mark on the runway and taxi track. As they were exiting after delivering the attack, Nos 3 and 4 found a Gnat closing in behind them, with guns blazing. Thanks to their swift Mirages, they were easily able to get out of harm’s way. Mirages continued with the airfield strikes, flying for five more days. A mission each was flown on 5, 6, 8, 9 and 10 December. Awantipura airfield was added to the usual list of Amritsar and Pathankot. Wg Cdr Hakimullah, alongwith attached senior squadron pilots, Sqn Ldr Rao Akhtar and Sqn Ldr Arif Manzoor alternated as mission leaders for these subsequent strikes. With the threat of enemy interceptors increasing, it was decided to add a pair of escorts during the airfield strikes. Altogether, 38 strike sorties (including 8 escorts) were flown by Mirages against three forward airfields. This was almost one-fourth of the total daytime counter-air effort of 158 sorties flown by the PAF. As stated earlier, these airfield strikes were largely disruptive in nature and served the purpose of softening up, before the actual neutralisation that was to come later with the army’s offensive. Seen in that context, they do not seem measly in quantum, though where they fell short was in the ‘punch’. There is no reason to doubt the IAF assessment of the effects as “negligible/slight damage.” The runways were never out of operation for more than a few hours. The damage could have been longer lasting if special runway penetrating ordnance had been used, as the Israeli Air Force had done in 1967. Non-availability of such weapons led the PAF to resort to conventional iron bombs which would bounce off the runway and explode above the surface, causing more blast and less breach. Also, delivery from shallow dive angles to avoid exposure to Anti Aircraft Artillery (AAA) made the bombs skip off the surface even farther. The disruptive raids seem well worth the effort, however, considering that operational and maintenance activity on IAF forward bases was hampered, and no PAF aircraft was lost while conducting these very dangerous missions. On a few occasions when enemy interceptors managed to get behind an odd Mirage, the latter was able to outpace them, much like Dassault had imagined in his desert vision of a mirage whereby, “enemy pilots should see it but never catch up with it!”

Defending the Skies

Despite a biggish nose which housed a sizeable antenna promising long range pick-up at higher altitudes, the Cyrano II radar of the Mirage lacked the ability to distinguish low flying targets against ground clutter. This drawback rendered the Mirage completely dependent on ground-controlled interception at low level, much like its spares-stricken counterpart, the F-104. PAF’s five low level ground radars could cover just 7% of the eastern border of West Pakistan and were, therefore, deployed at the main bases and a few vulnerable approaches only. Air defence was, thus, largely a function of Combat Air Patrols (CAPs) being able to respond to chance pick-up of low flying targets by ground radars. Once vectored on to its target by ground control, the Mirage could accelerate fast enough to chase an intruder for whom there was little hope of escape. The test of the Mirage’s capabilities as an interceptor came on the night of 4 December, when Flt Lt Naeem Atta was scrambled from Mianwali. The ground controller, Flt Lt Khalid Kashmiri, vectored Atta on to an intruder heading west, towards Mianwali. The controller was able to position the Mirage three miles astern of the low flying target, but even with a nearly full moon, there was no prospect of visual contact at that distance. As the Salt Range loomed ahead, the target started climbing to avoid the hilly terrain. Fortuitously for Atta, this meant that the target was also easing out of ground clutter and there was a good probability that it would be ‘painted’ by the Cyrano radar. Unknown to Atta, his radar had been in standby mode, as he had not been careful in selecting his switches in a hurry. On the radar controller’s reminder, Atta rechecked the selection to transmit mode, and was soon able to report a blip on his radar scope at an optimum IR-missile shooting distance of one-and-a-half mile, dead tail-on. Following radar lock-on, the missile’s seeker head swung to the heat source, and a growl in Atta’s earphones confirmed a launch-ready condition; the intruder’s fate was sealed. Moments after launching the AIM-9B Sidewinder, Atta saw a huge fireball silhouetting an aircraft in the night sky. Next morning, the wreckage of a Canberra (IF 916) was confirmed at the village of Nara located at the western edge of the Salt Range, not too far from Khushab town. The aircrew, including the pilot Flt Lt Lloyd Sasoon and navigator Flt Lt Ram Advani, belonging to the Agra-based Jet Bomber Conversion Unit, were killed on impact. [1]

Not far from Mianwali is Sakesar, a small PAF Base perched on the picturesque Salt Range at an elevation of 5,000 feet. The Base housed a high-powered FPS-20 radar as well as the vital Sector Operations Centre – North. At mid-day on 5 December, the IAF had made an attempt at attacking the radar, which cost it dearly, as two Hunters were shot down by a patrolling pair of F-6s. Later that afternoon, a lone intrepid Hunter was able to sneak in for a successful rocketing attack. After the attack a clean getaway for a singleton, right under the noses of patrolling interceptors, was an improbable prospect. As expected, the Hunter was intercepted by two Mirages scrambled from Mianwali. The pair was led by Flt Lt Safdar Mahmood, with Flg Off Sohail Hameed as his wingman. Diving down from the hills, the Hunter had built up speed, but not enough to elude the far swifter Mirages. With the help of instructions from the ground controller Flt Lt Shaukat Jamil, Safdar was able to catch up and settle behind the Hunter, to start his shooting drill. A couple of well-placed bursts of the 30-mm cannon got the Hunter smoking. As Safdar held off while watching his quarry in its last throes, Sohail picked up the smouldering aircraft and let off a Sidewinder missile to finish it off. Just before the aircraft impacted the ground, the pilot ejected but it was too late. Sqn Ldr Jal Mistry of No 20 Squadron was found fatally injured. The wreckage of the Hunter (A 1014) was strewn near the small town of Kattha Saghral.

Chamb was one of the few sectors where Pak Army had made significant advances and the Indian XV Corps desperately sought destruction of heavy guns that had been reported in the area. On 6 December, a pair of Su-7s from Adampur-based No 101 Sqn was tasked to locate and destroy the guns. The Su-7s sought out what appeared like hutments concealing the artillery pieces and were rocketing the place. Flt Lt Salimuddin Awan and his wingman Flt Lt Riazuddin Shaikh, who were patrolling in their Mirages over Gujranwala-Sheikhupura area, were vectored by ground radar onto the two Su-7s. Salimuddin, who was carrying a R-530 radar-guided missile alongwith two Sidewinders, decided to get rid of the bulky weapon by just blindly firing it off, so as to lighten up for the chase. Spotting the Mirages, the Su-7s jettisoned their drop tanks and rocket pods, and started exiting east. With the Su-7s doing full speed, a long chase ensued till Riazuddin found himself close enough to fire a missile, but it went straight into the ground. Salimuddin then moved in, and on hearing the lock-on growl, pressed the missile launch button, not once but twice, to be sure. Two Sidewinder missiles shot off from the rails, and moments later, Riazuddin called out that one of the Su-7s had been hit. Salimuddin instantly switched to the other Su-7 and fired his 30-mm cannon. Just then, Salimuddin noted the outlines of Madhopur Headworks near Pathankot, which was not surprising, as they had been chasing the Su-7s for several minutes inside enemy territory, along the Jammu-Kathua Road. Recollecting themselves, the Mirages turned back and recovered at Sargodha with precariously low fuel. Monitoring of VHF radio confirmed a message transmitted to Adampur that an Su-7 had been “fired at … the pilot ejected”. It was later learnt that the wingman, Flt Lt Vijay Wahi had succumbed to his ejection injuries. The leader, Sqn Ldr Ashok Shinde, was lucky to bring back his Su-7 which had been damaged by bullet hits. High-speed pursuit was a forte of the Mirage, a lesson learnt by the IAF the hard way, and one time too late.

Mirages flew a total of 317 air defence sorties (221 during day, 96 at night) which was 18% of the overall air defence effort. [2] With three IAF aircraft shot down, the Mirage kill rate, based on the total air defence sorties flown, came to be 0.95%. This compares quite favourably with kill rates of other PAF fighters which performed air defence missions:- F-86F: 1.2%, F-86E: 1.1% and F-6: 0.74%.

Scouting the Troops

PAF had three Mirage IIIRs, which were equipped with five OMERA Type 31 optical cameras mounted in the nose. With a Doppler navigation radar available, getting to a destination was fairly easy. Magnesium flares provided enough illumination at night to confer a round-the-clock tactical reconnaissance capability. The number of aircraft was, however, on the low side and did not sufficiently cater for unserviceabilities. A month prior to the outbreak of all-out war, the PAF had started to fly cross-border photo recce sorties, some of which were in the vital Chamb Sector, where the Pak Army’s 23 Division had planned a secondary ‘diversionary’ offensive. With the disposition of forces well-known, the attack resulted in significant advances that threatened India’s overland links to Kashmir, besides depriving Indian forces from establishing a launch pad for offensive operations towards the vital lines of communication passing through nearby Gujrat. Early in the war, another important breakthrough came in the Suleimanki-Fazilka Sector, where 105 Independent Infantry Brigade (IV Corps) was able to surprise the Indian ‘Foxtrot’ Force, and made a firm foothold in the area of Pak II Corps’ planned main offensive. While the Indian forces desperately carried out repeated counter attacks, PAF Mirages conducted regular photo recce missions in Ferozepur area to update the ground commanders about Indian reinforcement efforts aimed at vacating the incursion. In the event, a badly demoralised and confused Foxtrot Force could not make any headway and the Pakistani brigade was able to safeguard the vital Suleimanki Headworks, which was only a mile from the border.

In preparation for the main offensive, PAF Mirages fervently conducted photo recce missions along Ferozepur-Kot Kapura, Ferozepur-Fazilka and Fazilka-Muktasar railway networks, as well as in general areas of Ferozepur and Sri Ganganagar, for the latest disposition of forces. An important mission involved recce of crossing points over Gang Canal for a careful scrutiny of obstacles across the waterway that could possibly impede the movement of II Corps. The main offensive could, however, not materialise as explained later, and most of the photo recce effort was rendered worthless. Two pilots who played a sterling role in the photo recce operations were the squadron’s ‘slide rule wizards’, Sqn Ldr Farooq Umar and Flt Lt Najib Akhtar. Of the 30 photo recce sorties (besides 15 escorts) flown by No 5 Squadron before and during the war, 22 were considered successful. [3] Although most of the singleton recce Mirages were escorted by another Mirage, yet some of the missions had to be aborted due to intense enemy air activity. In Shakargarh Sector, a few night recce missions were attempted with partial success. In one such mission on the night of 11 December, an IAF MiG-21 scrambled to intercept a Mirage flown by Sqn Ldr Farooq Umar, ended up shooting down one of its own MiG-21s flown by Flt Lt A B Dhavle, which was patrolling in the vicinity. Four-odd Bomb Damage Assessment missions were also flown following the initial strikes on runways. These helped in better planning of subsequent airfield strike missions.

Interdiction of Supplies

One of the hugely successful missions of the war was an attack on Mukerian Railway Station. On 15 December, Wg Cdr Hakimullah was tasked to lead a four-ship mission to attack Bhangala Railway Station on Jalandhar-Pathankot railway line. After pulling up for the attack, he was dismayed to discover that there was no rolling stock in sight, but he decided to try his luck further south along the railway line. Having flown a mere 30 seconds, he overflew Mukerian Railway Station which was bustling with trains. Peeling off into the attack pattern, the four Mirages set themselves for single-pass dive attacks with two 750-lb bombs each. According to Hakimullah’s estimate, there were at least 100 freight bogies latched to different trains berthed adjacent to each other. The Mirages released their bombs one by one, though No 4, who had hung ordnance, pulled off dry. The impact of the bombs on fuel and ammunition laden trains was so furious that the blasts shook the aircraft; No 2’s drop tanks sheared off with the shock wave but he was able to fly back without any further damage. The Mirages had so far been striking at shallow targets, but with the time for the main offensive running out, it was decided to use them more audaciously. It was ironic that one of the most significant interdiction missions was also the one and only flown by Mirages, before the curtain fell two days later.

Drop Scene

Pakistan Army’s plan in the west called for the beginning of offensive operations five or six days after an Indian attack in the east. These, however, were meant to be secondary operations, essentially distractions, designed to fix the enemy and to divert his attention away from the intended site of the main attack by II Corps. With one armoured and two infantry divisions, II Corps was to strike into India from the Bahawalnagar area approximately three days after the secondary attacks. II Corps was to drive east to cross the international border, before turning to the northeast to push for Bhatinda and wishfully, beyond. It was expected that most of India’s armoured reserves would have become embroiled in Pakistan’s defences in the Shakargarh salient during this three-day interval between the secondary attacks and the main effort. After much prodding by the Army’s field formation commanders as well as the PAF C-in-C, the vacillating GHQ reluctantly issued orders for II Corps to shift to its forward assembly areas on 14 December; elements of 1 Armoured Division began to move the following day. By this time, however, the other major component of II Corps ie, 33 Division, had already been detached to reinforce the beleaguered I Corps in the north and 18 Division in the south, where things were not going well for the Pakistan Army. As a consequence, II Corps was deprived of almost one third of its striking power before the offensive had even begun. On the evening of 16 December, however, new instructions arrived from GHQ, “freezing all movements” until further notice. Following capitulation of forces in the Eastern Wing, Pakistan accepted a cease fire on 17 December. Mirages – which were expected to reduce the IAF’s weight of attack by neutralising 4-5 IAF airfields once the main offensive was underway – could, thus, not be utilised for the critical task that had been meticulously planned for months.

Report Card

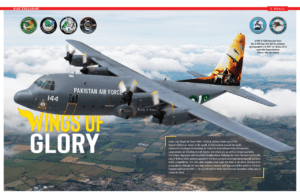

During the 14-day war, Mirages flew a total of 390 sorties which was 13% of PAF’s overall war effort of 2,955 sorties. [5] For a relatively new and modern weapon system, the Mirage achieved a modest aircraft Utilisation Rate of 1.6 sorties per aircraft per day during the war. [4] While it fell short of the planned 2.2 daily sorties, it reflected a cautious conduct of the war whereby the PAF was held back, so that everything could be thrown in during the army’s main offensive which, in the event, never came through. Wg Cdr Hakimullah, who very ably commanded the Mirage squadron during the war, and also led several dangerous missions in enemy territory, was awarded the Sitara-i-Jur’at (Star of Valour). That coveted award also went to Sqn Ldr Farooq Umar, the senior flight commander of the squadron, who had flown many useful photo recce missions in enemy areas infested with patrolling fighters. The three pilots who shot down IAF aircraft were content with having joined the elite club of fighter pilots with aerial kills. A month after the war, the PAF was able to line up 22 Mirages for all to see on the tarmac at Sargodha, while the 23rd Mirage was under maintenance in a hangar.[6] The impressive sight belied claims of any losses that had been incurred by the Mirage fleet during the war.

References:

[1] The Canberra’s ‘Orange Putter’ tail warning radar (an active device) was prone to picking up ground clutter, and was usually turned off by the pilots at lower altitudes. It is likely that Sasoon had also turned it off, to avoid false alarms that would have been triggered over the hilly terrain.

[2] Official PAF Records.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Utilisation Rate is based on an average aircraft serviceability of 75%. The Mirage-III wartime UR is calculated thus: UR = 395 sorties ÷ 17 aircraft ÷ 14 days = 1.6.

[6] A picture of the lined-up Mirages appeared in Air Enthusiast, May 1972 issue.