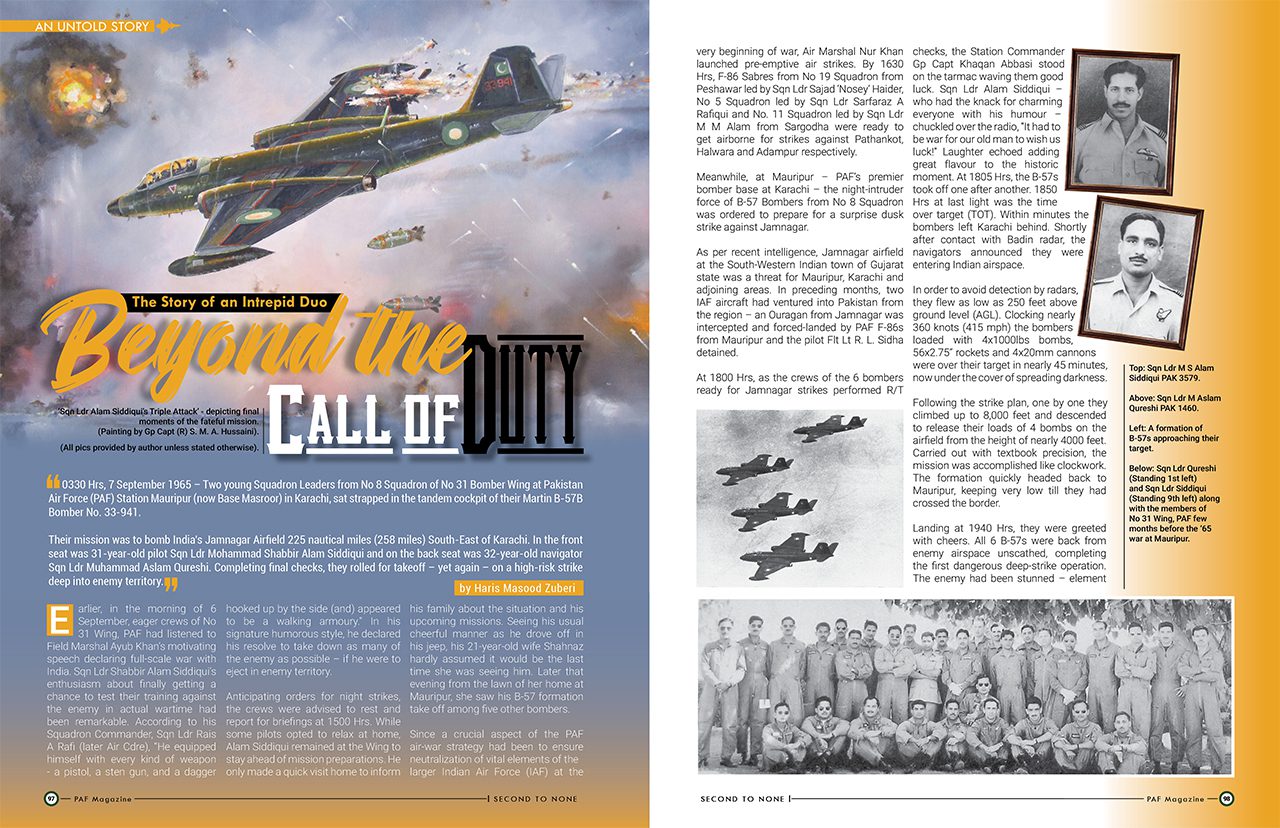

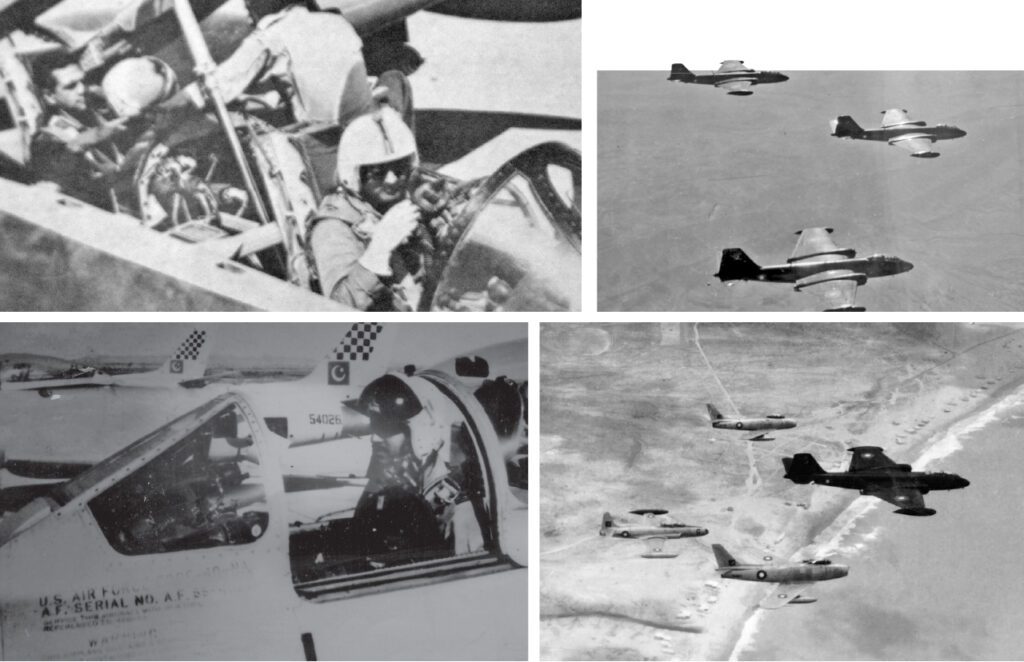

0330 Hrs, 7 September 1965 – Two young Squadron Leaders from No 8 Squadron of No 31 Bomber Wing at Pakistan Air Force (PAF) Station Mauripur (now Base Masroor) in Karachi, sat strapped in the tandem cockpit of their Martin B-57B Bomber No. 33-941.

Their mission was to bomb India’s Jamnagar Airfield 225 nautical miles (258 miles) South-East of Karachi. In the front seat was 31-year-old pilot Sqn Ldr Mohammad Shabbir Alam Siddiqui and on the back seat was 32-year-old navigator Sqn Ldr Muhammad Aslam Qureshi. Completing final checks, they rolled for takeoff – yet again – on a high-risk strike deep into enemy territory.

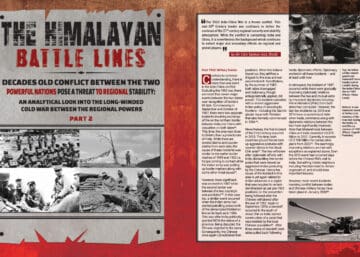

Earlier, in the morning of 6 September, eager crews of No 31 Wing, PAF had listened to Field Marshal Ayub Khan’s motivating speech declaring full-scale war with India. Sqn Ldr Shabbir Alam Siddiqui’s enthusiasm about finally getting a chance to test their training against the enemy in actual wartime had been remarkable. According to his Squadron Commander, Sqn Ldr Rais A Rafi (later Air Cdre), “He equipped himself with every kind of weapon – a pistol, a sten gun, and a dagger hooked up by the side (and) appeared to be a walking armoury.” In his signature humorous style, he declared his resolve to take down as many of the enemy as possible – if he were to eject in enemy territory.

Anticipating orders for night strikes, the crews were advised to rest and report for briefings at 1500 Hrs. While some pilots opted to relax at home, Alam Siddiqui remained at the Wing to stay ahead of mission preparations. He only made a quick visit home to inform his family about the situation and his upcoming missions. Seeing his usual cheerful manner as he drove off in his jeep, his 21-year-old wife Shahnaz hardly assumed it would be the last time she was seeing him. Later that evening from the lawn of her home at Mauripur, she saw his B-57 formation take off among five other bombers.

Since a crucial aspect of the PAF air-war strategy had been to ensure neutralization of vital elements of the larger Indian Air Force (IAF) at the very beginning of war, Air Marshal Nur Khan launched pre-emptive air strikes. By 1630 Hrs, F-86 Sabres from No 19 Squadron from Peshawar led by Sqn Ldr Sajad ‘Nosey’ Haider, No 5 Squadron led by Sqn Ldr Sarfaraz A Rafiqui and No. 11 Squadron led by Sqn Ldr M M Alam from Sargodha were ready to get airborne for strikes against Pathankot, Halwara and Adampur respectively.

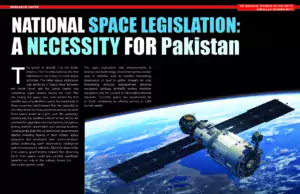

Meanwhile, at Mauripur – PAF’s premier bomber base at Karachi – the night-intruder force of B-57 Bombers from No 8 Squadron was ordered to prepare for a surprise dusk strike against Jamnagar.

As per recent intelligence, Jamnagar airfield at the South-Western Indian town of Gujarat state was a threat for Mauripur, Karachi and adjoining areas. In preceding months, two IAF aircraft had ventured into Pakistan from the region – an Ouragan from Jamnagar was intercepted and forced-landed by PAF F-86s from Mauripur and the pilot Flt Lt R. L. Sidha detained.

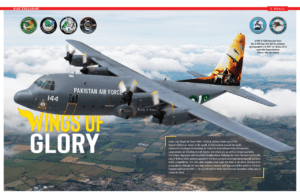

At 1800 Hrs, as the crews of the 6 bombers ready for Jamnagar strikes performed R/T checks, the Station Commander Gp Capt Khaqan Abbasi stood on the tarmac waving them good luck. Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui – who had the knack for charming everyone with his humour – chuckled over the radio, “It had to be war for our old man to wish us luck!” Laughter echoed adding great flavour to the historic moment. At 1805 Hrs, the B-57s took off one after another. 1850 Hrs at last light was the time over target (TOT). Within minutes the bombers left Karachi behind. Shortly after contact with Badin radar, the navigators announced they were entering Indian airspace.

In order to avoid detection by radars, they flew as low as 250 feet above ground level (AGL). Clocking nearly 360 knots (415 mph) the bombers loaded with 4x1000lbs bombs, 56×2.75” rockets and 4x20mm cannons were over their target in nearly 45 minutes, now under the cover of spreading darkness.

Following the strike plan, one by one they climbed up to 8,000 feet and descended to release their loads of 4 bombs on the airfield from the height of nearly 4000 feet. Carried out with textbook precision, the mission was accomplished like clockwork. The formation quickly headed back to Mauripur, keeping very low till they had crossed the border.

Landing at 1940 Hrs, they were greeted with cheers. All 6 B-57s were back from enemy airspace unscathed, completing the first dangerous deep-strike operation. The enemy had been stunned – element of surprise was evident by absence of fighter interceptors and more surprisingly anti-aircraft artillery (AAA). This observation on the first bombing mission proved crucial for ensuing operation. It was decided to continue a ‘Bombing Shuttle’ over Jamnagar through the night, this time as single bombers following each other at intervals till dawn. Each crew who had flown the dusk mission was to fly a second sortie. Owing to the darkness and the enemy being on full alert conditions were much riskier.

As the aircraft fuelled and reloaded, Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui hopped into another B-57 aircraft (No. 33-945) with call-sign ‘Zulu 753.’ Among the six pilots who had just returned from the dusk mission, he was the first to head back to the target. This time with the senior navigator Sqn Ldr Aslam Qureshi, who held the appointment of the Wing Navigation Leader. He had earlier been among the crews reserved for Peshawar when the dusk strike went ahead. Since the move to Peshawar with No 7 Squadron was called off, he was keen to fly his first war mission.

They took off at 2240 Hrs and crossed the border in darkness. The expert navigator had no difficulty reaching the target head-on and on time, despite the navigation difficulties involved in low-level deep night-strikes. Once above the target, they dropped bombs at approximately 2325 Hrs. With the mission successfully completed they quickly headed back. Winning against odds once again, they landed at Mauripur at 0025 Hrs – initial moments of 7 September 1965.

All crews returning from second missions were supposed to rest till further orders. Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui got back to the Operations Room filled with an extraordinary energy to keep contributing to the effort. Then holding additional responsibility of the Wing Operations Officer, he had been on his feet since he reported for duty early in the morning on 6th. Throughout the day he had kept busy with arrangements. He had played his role very well on the first day of the war and now deserved to head home.

Instead, at 0300 Hrs, his Wing mates were not surprised to find him lurking around in his flight suit – ready for more action. Since his return at 0025 Hrs, he hadn’t even considered going back to his anxious young wife and two infant sons. It was inconceivable for the perpetually dynamic Alam Siddiqui to leave in the midst of decisive action while some of his colleagues were still flying deep into Indian airspace. As he actively sought another chance to get airborne, fate presented him an ideal opportunity – The OC Wing, Wg Cdr Hameed Qureshi had been scheduled to take-off on his second mission at 0335 Hrs. However, since return from the earlier dusk mission, he had suffered a medical condition and seemed incapacitated. While the flight surgeon checked on him, crews were concerned for disruption of the planned sorties. Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui at once volunteered to go instead.

Incidentally, this sortie was scheduled last for the night. Although, he could have avoided flying for the third time within a span of 9 hours, he enthusiastically opted for this mission, fully aware there would be no break for him even the next day. With the Squadron OC in the air and the Wing OC getting medical assistance, he took initiative as a senior officer of the Wing. Instead of wasting time to brief fresh crews or ordering another pilot, while nobody stepped beyond the second mission, he chose to fly again himself. The significance of his decision to ensure this last raid was not delayed or missed turned out to be momentous – as discovered later through Indian accounts from Jamnagar.

His former OC Sqn Ldr (later AVM) Saeed A. Ansari who had also been his instructor during his Risalpur days, tried to dissuade him from volunteering to fly again. “They have not seen the target – I have just returned from there. I can cause more damage…” he said. Determined and decisive as he always was, Alam convinced Ansari with his typical smile and energetic handshake and drove off to the flight lines in his jeep.

Sqn Ldr Aslam Qureshi meanwhile, had been up to his own heroics. Right after landing from his first mission, he used his authority to assign himself the navigation slot on this last mission as well. While he could have avoided it on the pretext of having flown earlier or pressing responsibilities on ground, he rose to the occasion. Once settled with arrangements he had just reclined in an empty room when he was informed about Wg Cdr Hameed Quershi being unable to fly and Alam Siddiqui taking over. He quickly joined the pilot for briefings.

In the wee hours of 7 September 1965, this dauntless duo now rolled off Pakistan’s soil to give the enemy yet another pounding – true to the motto of their squadron ‘Ik Aur Zarb-e-Haidery.’ They took off for their target from runway 27 in B-57 No. 33-941 at 0335 Hrs bearing call-sign ‘Z-6.’ As the bulky dark warrior-aircraft aptly signed ‘Zulu’ took a sharp left turn heading 130 degrees, the sky was moon-lit. In all probability keeping in line with the profile followed by the night’s earlier sorties, they flew low at no more than 500ft AGL. At a speed of nearly 360 knots (415 mph) their aircraft fast approached Jamnagar. En route, they had radio contact with Sqn Ldr Rais A. Rafi who was exiting the area after his attack at 0340 Hrs. He advised them “Watch out for low clouds…use flares to light up the target.” Just as he had just done moments earlier.

The aircraft reached over the target at approximately 0415 Hrs Pakistan Standard Time – almost first light, nearly some 40 minutes after take-off from Mauripur, loaded with 4x1000lbs bombs to wreak havoc on the enemy airfield. According to procedure, the crew climbed up for the dive bombing to about 5000ft or more AGL and dived to release the bombs at about 3000 feet or less – first dropping flares to light up the target during descent. Owing to Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui’s zealous nature almost certainly going lower below the gathering clouds for precision. With the airfield below now lit up and visible they made the first bombing run and dropped 2x1000lbs bombs over the airfield. The flares were risky business – while they made the airfield below visible, they also lit-up the attacker for AAA gunners below.

Just so happened that when the lone ‘Zulu 6’ suddenly showed up diving through the clouds to deliver its fury over the enemy airfield, eight Seahawk fighter aircraft of the No. 300 Indian Naval Air Squadron (INAS) were preparing for a massive strike against PAF’s Badin radar installation at dawn on 7 September. The B-57 meanwhile making a quick circuit swiftly climbed and came in for another dive to release the 2 remaining 1000lbs bombs. By now the silence of the previously blacked-out airfield which had been on the receiving end of PAF’s wrath since 1900 Hrs (PST) opened its furious retaliation with AAA fire. As ‘Zulu 6’ dived in for the second attack, it was inevitably caught in an Ack Ack (AAA) barrage.

Flying through the fierce fireworks, hurriedly to get rid of excess weight the crew jettisoned the B-57’s 2 rocket launcher pods. They landed very close to the INAS Seahawks and have since been preserved by India as souvenirs of the PAF night-raid, as confirmed by Rear Admiral (Retd) Satyindra Singh in his book ‘Blueprint to Blue Water – The Indian Navy 1961-1965.’ Suddenly ‘Zulu 6’ suffered direct hits from Indian AAA below causing serious damage. The aircraft began to lose control. Already low, the now damaged bomber began losing altitude. Unable to pull through much farther, while clocking somewhere between 360 and 400 knots (415-460 mph) impact was now imminent. PAF B-57 No. 33-941 eventually hit ground and crashed in an agricultural field 10 miles East of the Jamnagar airfield – apparently martyring both the courageous officers on impact.

However, unusual absence of prompt news about the bomber and its crew officially received from India following the loss initially caused helpless bewilderment. As a result, the fate of this intrepid duo remained uncertain for days and eventually decades. IAF’s unexpected tardiness in claiming a ‘kill’ caused speculations. Combined with the details on absence of Ack Ack or interceptors experienced on previous raids, the presence of low clouds, very low flight profile and possible fatigue due to the pilot flying third mission fostered assumptions about ‘Z6’ including the bizarre possibility of having crashed into the Arabian Sea en route.

In India however, the fate of this bomber and its crew was certain. Ack Ack had indeed claimed B-57 No. 33-941 kill which was acknowledged by the Indian authorities shortly afterwards. Indian military had retrieved a diary attributed to the crew. Images of its pages were immediately released to the media. Naturally utilizing propaganda value in the middle of war, various Indian English and Hindi newspapers had published news of the shooting down along with images of the diary pages as well as the B-57 wreckage declaring that the crash had taken place very close to Jamnagar airfield (The Statesman, Calcutta & Delhi, 13 September 1965; The Times of India, Bombay & Delhi, 14 September 1965; Indian Express, Madras, Bombay, Delhi, 14 September 1965).

When a POW exchange took place between the two nations in January 1966, India handed over a fragment of an oxygen mask attributed to the pilot along with the wallet of Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui, in a distressed condition but still holding its contents including family photographs. The Government of Pakistan changed the status of the lost crew from MIA to KIA, but somehow the uncertainty regarding their fate perpetuated in the absence of an official verdict. In 2005 the acclaimed book ‘The India Pakistan Air War of 1965’ by P. V. S. Jagan Mohan and Samir Chopra revealed accounts including that of Air Cdre K. A. Hariharan, an IAF pilot then stationed at Jamnagar, who had witnessed the last bomber’s raid, the illumination by its flares and eventually its being hit by Ack Ack.

Another eyewitness Sqn Ldr Kesav Chandaran narrated, “Our Station Commander Gp Capt G. H. King had filed a kill report. The crew may have attempted crash landing as the B-57 crashed towards the road to Rajkot and hit a large tree – its tail may have been hit moments after they damaged a hangar.” Adding, “There was no fire on impact and a broken watch was recovered from one of the crew and kept at a museum somewhere.”

In 2006, 40 years after the September 1965 war, Air Cdre Najeeb Ahmed Khan (Retd) met Mrs Shahnaz Alam. Having been very close to Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui Shaheed, he was touched by his dear shaheed friend’s wife’s anguish and sentiments for her lost husband – even four decades later. He wrote to IAF requesting information and details about the fate of the crew from the fateful mission. In a historic gesture, then IAF CAS Air Chief Marshal S. P. Tyagi carried out exclusive research and officially informed that as per records, eye witness accounts of locals, images and material attributed to the wreckage and the crew it was certain that B-57 No. 33-941 had made it right over Jamnagar Airfield – dropped two bombs and was in second circuit to drop the remaining load when it was caught up in AAA – was inevitably hit, and minutes later crashed few miles across the airfield, martyring the crew. IAF further pin-pointed the crash site at an agricultural field 10 miles east of the airfield and facilitated a visit to the location. A documentary was produced by CNN-IBN showing the location and old pictures, including one from a local daily displaying the wreckage with Indian Navy officials beside it.

While plight of the fighter squadrons from initial missions in the north brought several heroes to the forefront by the very first afternoon of the war, achievements of bombers from the same night remained relatively under-explored. No 8 Squadron persevered in silence while its crews delivered the momentous tasks of preserving the defences of the south by offering IAF enough poundings to keep it on ground. During the war, two operational missions in a night were considered the limit. Sqn Ldr Alam Siddiqui had first taken- off at 1805 Hrs and for the third time at 0335 Hrs. Flying 3 combat missions within a span of 9 hours in the same night is accepted as a record. Especially during the 1965 and 1971 wars, as far as bombing missions were concerned.

The loss of two fighters of No 5 Squadron from Sargodha created legends – Sqn Ldr Sarfaraz A. Rafiqui and his wing-man Flt Lt Yunus Hussain. Within hours they were followed by Sqn Ldrs Alam Siddiqui and Aslam Qureshi of No 8 Bomber Squadron from Mauripur. Together it was these heroes whose courage and devotion on the very first evening of the war inspired fearlessness and shaped the psyche of PAF’s air-warriors facing an enemy superior in numbers.

Facts took nearly five decades to become evident. Had this last raid been called-off due to crew discrepancy, the INAS crew in Jamnagar would have caused devastation. This dauntless duo managed to annihilate the Indian assault when they ferociously descended on the enemy through the clouds just when the Seahawks were preparing for the raid. Damage to the runway and control tower left no time for them to reorganize and make it to Badin before dawn. Their sacrifice not only preserved national prestige but also contributed to the significant edge which PAF maintained through the war. As Rear Admiral (Retd) Satyindra Singh of Indian Navy puts it, ‘Had the eight Seahawks at Jamnagar been allowed to bomb the ‘seeing-eye’ of PAF and its air defence establishment at Badin (…) on the morning of 7 September the war would have been over much earlier and (Indian) aircraft losses would have been minimized.’

In having so gallantly laid their lives, they added a golden chapter in the glorious history of PAF which is rich with such traditions of selfless devotion literally beyond the call of duty.