Today, nearly two dozen Pakistan Air Force C-130 transport aircraft crisscross the skies above us. It’s one of the best aircraft in history and its life span is exceptional – almost forever. But what is the explanation behind this record of longevity? One of the secrets of its stunning performance is the heavy checks it undergoes at the 130 Air Engineering Depot, Nur Khan Air Force Base. Intensive inspections, gigantic technical appraisals the Hercules is submitted to, during which the transport plane is completely stripped down and overhauled by taking out all its systems, and returning the Hercules to full working condition – it all happens in the hangars at No 130 AED. Delays in overhauling a Hercules are out of the question.

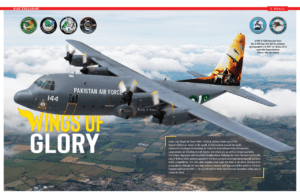

The PAF’s primary transport is the C-130. Over its 50 years’ service history, the C-130 has proven itself capable of carrying impressive amounts of loads including airframes and engines of JF-17 aircraft from China. Operations tend to run swiftly and smoothly when it comes to the Hercules. PAF has worked through the years to modernize the cargo plane in essentially every way. But like all aircraft, they are subject to damage. Severe weather, unforeseen accidents, plus distress of everyday operations all take their toll on these powerful machines. Aircraft structural repair plays vital role for these planes to sustain. To keep the PAF’s fleet of C-130s airborne, the 130 AED, keeps them serviced well and are run on strict schedules for repair and maintenance work.

“AED is where all of PAF’s C-130s come to be stripped down, refurbished, repainted and rebuilt, when it’s time for some heavy-duty maintenance. It’s one of the most fascinating facilities,” said Gp Capt Azhar Mahmood, who is OC 130 Air Engineering Depot, PAF, at the Nur Khan Air Base.

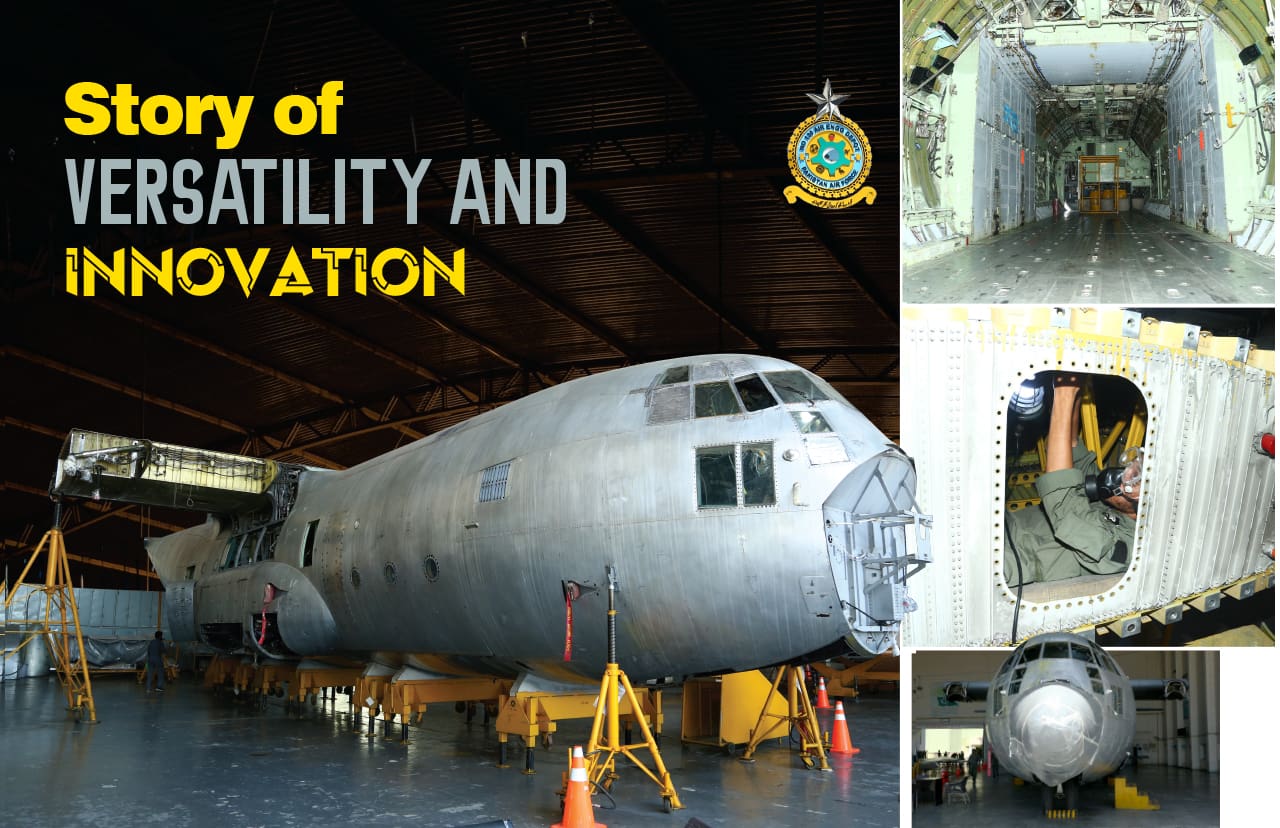

On a warm Friday morning in May, the Second to None team had the chance to see in person what it took to keep the C-130s flying, and meet the engineers and technicians, whose job it was to look deep into the structural components of decades old airplanes. There was constant flow of activity in one of the two Air Engineering Depot (AED) hangers. Several dozens of specialists in the work of totally dismantling the monster, had stripped a Hercules Tail No 4148, of its wings and the vertical stabilizer. Thousands of round trips and flight hours in the air had left their mark on this beast. The technicians knew it better than anyone. It was a monumental surgical operation, carried out by engineers and technicians, always strictly according to the rules, high precision work, top of the range services and detailed plans.

“The Hercules is one of the largest and oldest military planes in its class. In fact, Pakistan is one of the fewer countries in the world flying B and E variants of the C-130. In most of the countries, they are museum exhibits,” said Grp Capt Azhar Mahmood, who is the OC 130 Air Engineering Depot, PAF, at the Nur Khan Air Base.

As one job made way for another inside the aircraft so it did outside. Sqn Ldr, M Omer Shahid, who is the Chief Maintenance Officer of No 130 AED, PAF and his colleagues painstakingly scanned every inch of the outer skin. Even inconspicuous damage could cause serious problems. Many covers had already been removed and work continued under the shell. No one had checked here for six years. “Engineers look for slightest deformation or signs of wear. We look at everything or something will get overlooked,” said Sqn Ldr Omer Shahid.

On Dock B, another colossus had been disassembled. Perched on hydraulic jacks and work platforms placed at different heights around the plane over 100 men were in action. Every detail was controlled because what looked like a scratch could have serious consequences. For decades this Hercules, Tail No 4148 has been a critical air mobility asset allowing combat forces to be quickly deployed for training as well as humanitarian assistance to any location in the country and in the world.

“To some it may only be a scratch. For us its serious structural damage,” he said Sqn Ldr, M Omer Shahid. Under the floor and running along its walls revealed an 11 to 12 kilometers long network of wiring. Cables outside of tolerance range would have to be replaced to bring the aircraft back to its normal configuration – flight command radio, fire detection cables, and so many more connections, all verified one by one. Even the fuel cells were inspected, from the inside. The engines, however, were transported to the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex (PAC) that supplied numerous parts for the C-130s, the officer explained.

Damage to the sloping longeron had compromised structural integrity of this heavy lifter. “Until five years ago, it used to be replaced with a new one. Then the AED figured it could be repaired as per publications and certified by OEM, saving massive costs on new parts,” Omer Shahid elaborated.

This C-130 Tail No 4148, was inducted in December 2022 and was on 50 percent inspection. Engineers particularly scanned the bulkhead panels, an important structural component subjected to excessive corrosion and vibrations. Floor panels removed, dents, cracks, and loose rivets, were all circled with blue marker and tagged and weathering identified in the wheel wells.

One of the Sqn Ldr’s colleague had a dangerous job. His workplace that day was the interior of the left wing. Where he lay, there is usually thousands of gallons of jet fuel. There are no least popular tasks and sometimes just a lot of work. Every second is used until departure.

At the AED, most rewarding is being part of something so big, to see the aircraft go from grounded to pieces to airworthiness in less than a year’s time. It’s rewarding and exciting, the team members of AED said.

It doesn’t only take a book that tells them how to perform a task, they have to use a little brain power to put things into action, writing the book as they go. Spending every minute of every day for almost a whole year allowed ground crews to see the little bits and pieces they did not usually get to see. “It brings you closer to the aircraft. Makes you actually care about it and the crews invest so much time in it that it becomes our baby,” Azhar Mahmood said.

One could feel the cutoff date getting closer and the aircraft had to be delivered. “You can feel the effervescence especially near the final days of handing over the aircraft to the pilots,” said Sqn Ldr Ubaid Majid, who is Oi/C A/C Production, Sqn No 130 AED, Nur Khan Air Force Base, Chaklala.

Delays were expected when spares were not easy to get hold of. If the teams did not meet the deadline, the grounding period increased. The induction of the next aircraft depended on production of the previous aircraft, the officer explained.

In the last 12 to 15 years, there were 24, 000 entries of structural defects registered. In one corner sat a repaired engine mount. In the past, to replace it with a new one set the air force back $50, 000. A rainbow fitting, disassembled, also repaired indigenously and confidently saved the air force another $100, 000. A new workshop enabled engineers and technicians to overhaul fuel cells in house, which otherwise set the PAF back Rs5 million to Rs6 million for transportation alone, saving two sorties to Karachi.

“Even minor faults are guaranteed to last for six years,” Sqn Ldr Ubaid Majid said proudly.

For the next part of the tour, the Second to None team saw highly advanced pieces of tech at the Non-Destructive Inspection (NDI) section. And if you liked playing with microscopes as kids, you’ll love this one. At the Nur Khan base scanning machines can detect cracks and irregularities in aircraft parts that are not visible to the naked eye. “Aircraft like the C-130 were built decades ago. By the time they retire it could be many years that these things are flying. So naturally parts of the aircraft are going to have damages to the structural components. With the help of these instruments technicians deep dive to see if there’s any instability, cracks or corrosion that requires to be fixed,” said Sqn Ldr Ubaid Majid.

The Second to None team got to see the hands-on maintenance, the science and technology – ultrasonic devices, x-ray gizmos and magnetic testing behind fixing the old aircraft. It was like an art form, having to deal with a lot of corrosion and holes in the aircraft. “It’s a new adventure every time. No repair is ever the same,” said Sqn Ldr Ubaid Majid elaborating that there was almost nothing they could not make and fix at the 130 AED where the crews were trained to maintain and repair the malleable and ductile and metal.

Since the induction of C-130 aircraft in Pakistan Air Force Inspection Repair as Necessary (IRAN) maintenance concept was implemented. Following the USAF experience of transformation from a conventional IRAN inspection to structurally intensive Programme Depot Maintenance (PDM) in 1979, the PAF also switched over to the new concept. This programme, besides fulfilling requirements of earlier IRAN inspection, also included extensive Non-Destructive Inspection (NDI) of critical structural areas.

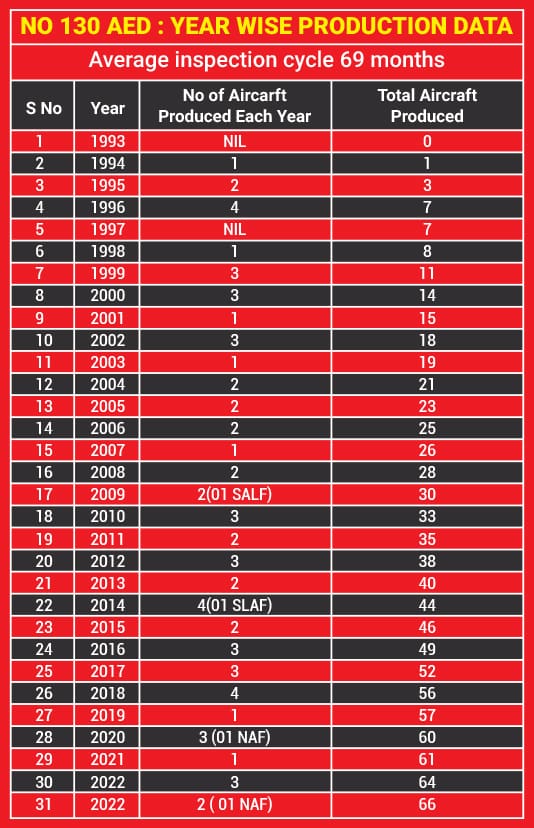

Initially, PDM inspections of PAF C-130 aircraft were accomplished by sending these planes abroad, at original equipment manufacturers’ authorized (OEM) facilities in Peru and Singapore. This resulted in exorbitant costs in terms of foreign exchange and also increased the grounding period of the C-130s, affecting the air transport operations of PAF. To achieve self-reliance and to avoid foreign dependence, the 130 Air Engineering Depot (AED), was established at the then PAF Base, Chaklala in 1993.

In little over two decades, the depot had completed PDM inspections of 66 aircraft including four C-130s of allied countries. The AED teams flew to Nigeria and Sri Lanka to overhaul their C-130 aircraft, in the respective countries. It’s an ongoing arrangement between the air forces of these countries with the PAF. “The only C-130s flying in the Nigerian Air Force are ones overhauled by Pakistan Air Force,” said Officer Commanding (OC) 130 Air Engineering Depot, PAF Grp Capt Azhar Mahmood.

It was this attitude of tackling challenges, overcoming impediments and the demonstrated commitment to prevail despite the odds that has earned PAF the nation’s respect.

The PAF maintains that the depot has played a pivotal role in the defence of motherland by accomplishing PDM and structural repair for PAF assets and other tasks assigned by Air Headquarters from time to time in a highly professional way by keeping safety as paramount. It has evolved into a viable engineering organization of excellence for the PAF’s transport fleet and is able to mark its potential regional repair center for C-130 aircraft.

Today, the entire PAF C-130 fleet has been modified to glass cockpits or integrated avionics upgrade programme (IAUP) and are being further improved to advanced settings such as Communications Navigation Systems (CNS) 2020, following western operational requirements. These modifications were mandatory for long haul transport operations.

After 69 months of flying, costs of one PDM stand at $10 million to $12 million compared to $35 million to $40 million per year, if the aircraft was sent abroad for complete structural overhaul.

It’s been an impressive exercise. Taken apart and put back together, it’s these overhauls carried out by highly skilled engineers and technicians that PAF can provide maximum safety to its flying crews thus making C-130 one of the safest planes. These heavy checks are not only technical challenges but also recount remarkable stories of men and women united in their passion for the air force.

Outside on the tarmac of the Nur Khan air base, another C-130 was undergoing final functional check flights. Pilots verified if the fixes had been done correctly, and if not they would give feedback. But that has never happened. From the pilot’s seats electrical and hydraulic circuits were reconnected, systems rebooted, tested, radars verified one last time and unforeseen details were rechecked that could shake up schedules.

As the induction brought the PAF into the modern age, several variations and upgrades have been made over the years to the C-130s. This aircraft was used extensively and played an integral role in several dire situations. The restoration of the craft and the paint job had been carried out with precise historical accuracy and because of that an important piece of history could be viewed today in its original form. If given a chance to see these remarkable pieces of history in person, one would pause for a moment to realize and respect the impressive journeys these aircraft have taken throughout their flight times.

For the airmen at AED, these are people passionate about their work. When they have a colleague struggling with an important and delicate task, there is solidarity from other team members, who come to help, suggest solutions, and offer different ideas. They are not the kind to go looking for the spotlight. They do their jobs just fine without getting pats on the back. Of course, when something breaks down that’s when the spotlight finds them. There’s passion, pride and sense of ownership. Thanks to this know-how, collaboration between engineers and technicians, the C-130 goes on improving, pushing to make the aircraft better and the future of C-130 is constructed.

As it returned from a brief test flight, and engine tests validated, the C-130 parked on the tarmac was declared operational. It was about to begin a new life. A challenge had been met bang on time. Its next flight to Sargodha, Karachi and back to Rawalpindi, had already been scheduled.