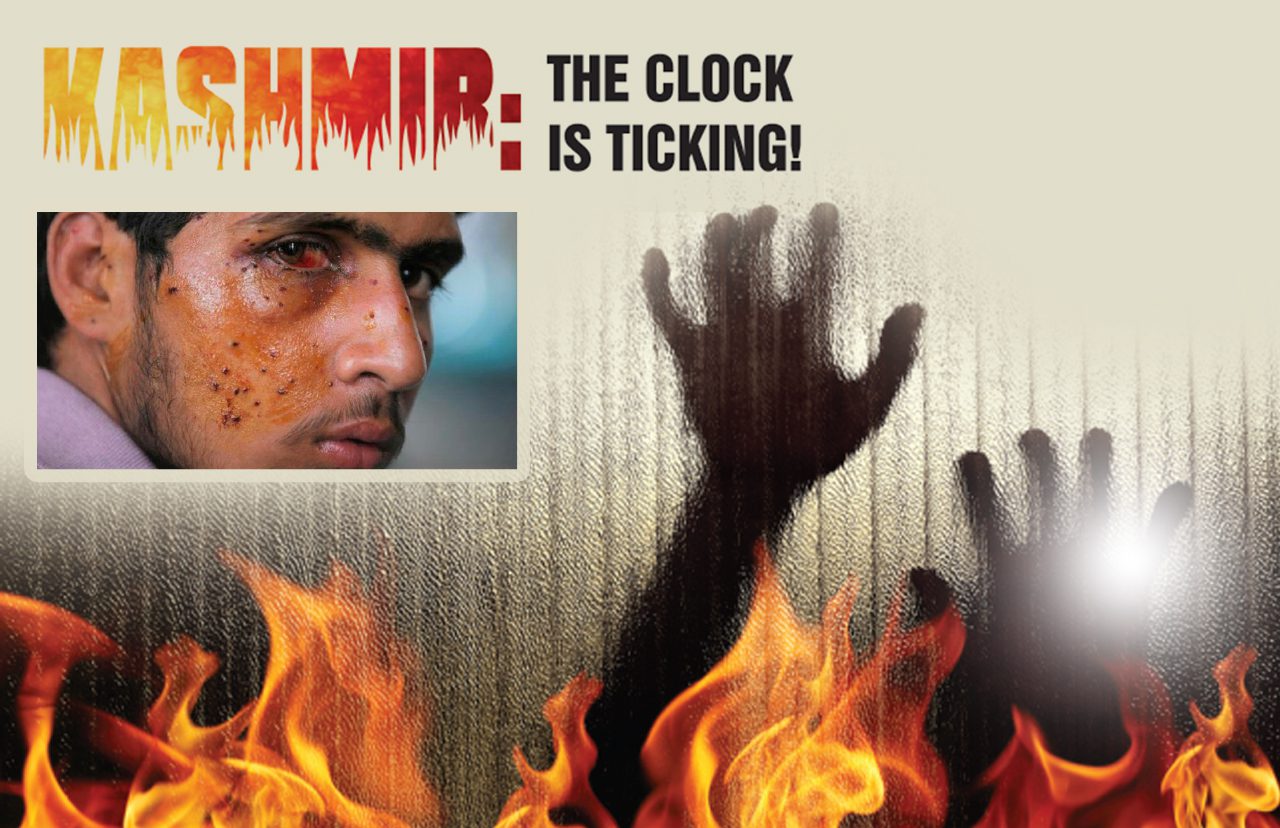

International Community Turns A Blind Eye.

The plight of the Kashmiris is one that Pakistanis are well aware of. From state-sanctioned abductions to outright executions, the Kashmiri people have no semblance of a safe existence. India’s atrocities in Kashmir have been documented and spoken about by countless human rights organizations from all over the world. However, India, instead of rectifying its tyranny, has shed any pretence of a conscience in Modi’s government and gone on a blood-soaked spree of new atrocities. The world needs to acknowledge and address the grim situation before it is too late.

The state of Jammu & Kashmir has drifted from international attention time and again due to geopolitical and geostrategic developments in the region. However, after the 1971 Simla Agreement, the international community decided to relegate and leave it as an issue between the two South Asian nuclear powers. The horrifying results of the war in East Pakistan seriously undermined Pakistan’s standing at international fora. However, as time went on and Indian atrocities in the disputed region increased incrementally, the international community was forced to review and take serious note of the historical dispute once more. United Nations Human Rights Office published a detailed report in June 2018 by Jordanian jurist Prince Zeid Raad al Hussein outlining the violations (including mass killings, kidnappings, forced disappearances, etc.) by the Indian forces in the region. They conducted these abuses unfettered with impunity due to the legal cover provided by the state of India. This cover was aided through the Armed Forces Special Protection Act (A.F.S.P.A.), extended to Kashmir since 1990.

The colonial-era state of Jammu & Kashmir was a unique case during the partition of the sub-continent. It was one of the few places where a Hindu ruler held sway over a majority Muslim population. However, culturally, linguistically, ethnically, economically, and geographically, Jammu & Kashmir was integrally connected with the territories that now form part of Pakistan. Kashmir’s main connections to the outside world were the Indus River and the Srinagar-Rawalpindi road, linking it to Pakistan. (i)

At the time of partition, the Indian state adopted the stance that a ruler could not join a dominion without its people’s consensus (ii). This stance put the Indian state in an unenvious situation concerning Kashmir’s accession. According to neutral observers, it could not annex Kashmir without taking the majority Muslim populations’ desires into consideration, which would have been in favour of joining Pakistan. This claim is backed by the account of Kashmiri scholar Bazaz, who observes “Speaking generally and from the bourgeois point of view, the Dogra rule has been a Hindu Raj. Muslims have not been treated fairly, by which I mean as fairly as the Hindus. Firstly, because, contrary to all ethics of treating all classes equally, it must be candidly admitted that Muslims were dealt with harshly in certain respects only because they were Muslims”(iii). This helps explain the Pakistan Movement’s widespread appeal in the 1940’s to most Kashmiris living under oppressive autocratic-fiscal conditions. Unfortunately, Maharaja Hari Singh was bent on changing the demographics of the Kashmir state. He did this by enabling a mass Muslim genocide in the territories that constitute present-day Poonch, starting August 24th 1947. Sensing discord in his dominion, the Kashmiri Maharaja requested Indian armed intervention. This unpopular action by the Maharaja resulted in an open revolt by the state’s inhabitants against the ruler. Prime Minister Mahajan of Jammu & Kashmir-in negotiations with Mountbatten-led Indian government-asked for the ‘Mysore-model’- in which a princely state remained a separate entity in the Union of India while the ruler became the constitutional head (iv). However, a compromise was reached between the parties to chalk out a tailored arrangement for the Jammu & Kashmir state. This consensus led to the insertion of Article 370 in the Indian constitution. Jammu & Kashmir issue had been taken up by the United Nations Security Council and the resulting stay was creating delays in the drafting of the Indian constitution. Therefore, the idea of Article 370 was floated, and it came to the fore as the clause of the Indian constitution on which the state of Jammu & Kashmir acceded to India. As part of the arrangement, Indian occupied Jammu & Kashmir was allowed its own constitution. The idea behind insertion of article 370 was that India would exercise limited legislative powers over Jammu & Kashmir and not enlarge its sphere of influence (from the specified subjects of Defence, Communications, and Foreign Affairs) without the people’s consent.

Nevertheless, Article 370 has been hollowed out over time as noted by renowned Indian journalist A.G Noorani in his book. The ‘hollowing out of Article 370’ has been undertaken through “ninety-four of the ninety-seven entries in the Union List being extended to Jammu and Kashmir as well as 260 of the 395 articles of the constitution being extended to the state” (v). In the State Bank of India vs. Santosh Gupta case dated December 16th 2016, the “Court reiterated that the President cannot issue an order ceasing to make Article 370 inoperative without the recommendations of the constituent assembly of Jammu & Kashmir”(vi). The constituent assembly of Jammu & Kashmir had already been dismissed in 1957. To overcome this complexity, the B.J.P. government came up with a legal innuendo designed to make Article 370 inactive while simultaneously retaining it in the constitution, thereby, in essence, abrogating it. The resulting situation created unforeseen issues for the right-wing B.J.P. government and its obstinate leaders. More importantly, the abrogation brought the dispute back to international attention. It also attracted China’s ire, which has led to a border standoff between the two Asian giants since 5 May, 2020.

To put things in context, Jawaharlal Nehru had earlier held negotiations with Sheikh Abdullah to win his support to join the Indian Union. In one instance, Nehru had also been arrested by Maharaja’s administration while on his way to meet Sheikh Abdullah. The Congress supremo was keen to resolve the Kashmir dispute expediently, in part, due to his Kashmiri roots. However, soon, he realized that Sheikh Abdullah was not budging from his stance of maximum autonomy for Kashmir. Then the British hastily withdrew in 1947, and sensing an opportunity, the Indian Prime Minister took advantage of the state of affairs. Subsequently, Nehru had the Kashmiri populist leader arrested in 1953. This antagonizing move initiated the rift between the Kashmiris and the Indian state, which continues to haunt the present-day South Asian geopolitical and geostrategic dynamics. The irony lies in the fact that in the early years, Indian leaders had even gone to the extent of suggesting that a plebiscite would be held at a future date when Pakistani armed personnel would withdraw from the state, which would give Kashmiris’ the right to even secede from the Union of India (vii). India objected to Pakistan’s decision for not pulling back its troops from Kashmir and obstructing the plebiscite’s conduct. In response, Pakistan reprimanded India to decline to a neutral withdrawal and instead focus on the plebiscite (viii). However, in the pre-partition days, the same Nehru made untiring efforts to secure the Kashmiri populace’s support by political promises of autonomy and self-rule.

In the backdrop of these events/circumstances, the international community attempted to resolve the seemingly intractable Kashmir dispute. Global powers’ efforts to resolve the Kashmir issue began only weeks after the conflict erupted in October 1947(x). The Kashmir dispute seemed tailor-made for the United Nations. It had all the ingredients that would garner international powers’ interest: colonial history, territorial ambiguity, and two states with powerful militaries seeking international community’s aid in resolving an issue regarding self-determination. However, it soon dawned upon global powers that the dispute could not be decided amicably. If Washington kept on promoting a role for the U.N., it was to keep its new ally Pakistan reasonably happy, and not because it believed that progress could be made.(xi) New Delhi, on the other hand, resisted internationalizing the issue and rejected Washington and other global powers’ offers.

The U.N. passed eighteen resolutions to help resolve the Kashmir dispute in the timeframe between 1947 and 1971. It established the United Nations’ Military Observers Group for India and Pakistan (U.N.M.O.G.I.P.). Several special rapporteurs, including Czech-American Josef Korbel and Australian diplomat Sir Owen Dixon held lengthy discussions with both sides to find an amicable solution to the enduring issue. Different out-of-the-box proposals were floated, including the Dixon plan, which called for a limited plebiscite in the Kashmir valley. Similarly, the Chenab formula was put forth by Pakistan, calling for demarcation of the state between the two South Asian neighbors along the Chenab River.

However, India saw no role for international intervention even though, ironically, it had initially gone to the United Nations’ Security Council itself, i.e., during the 1948 border war between the two states. After the Simla agreement succeeding the 1971 war, Kashmir-according to India’s interpretation-was to be treated strictly as a bilateral dispute between Pakistan and India.

If the dispute is positioned in the current geopolitical times, it can be safely said that it is solely the United States which has the economic and diplomatic clout to mobilize and channelize efforts to resolve this seemingly perennial dispute.[xiv] However, according to Professor Schaffer, despite its improved relations with the United States, India will always be warier of an outsider’s role than Pakistan. The dispute on Kashmir is emotive across the divide for various reasons. It garners support in Pakistan because of religious and cultural affiliation. Pakistan’s state narrative is that the Instrument of accession was a falsified document. On the Indian side, the territory is seen as an ‘integral part’ of secular India. India’s curfew and stranglehold in the region have resulted in the inhabitants’ inability to access necessary supplies such as medicine, food, and fuel. This has turned Kashmir into a mass concentration camp where more than 900,000 Indian security forces are deployed. Moreover, Indian use of the latest technologies for surveillance of Kashmiris is violation of their civil and personal liberties.

It can also ominously be concluded that the recent turn of events indicates that the international community has turned its face away from the Kashmir dispute and relegated it to only an ‘informal consultative session’ at the United Nations’ general assembly due to intense Indian lobbying. This does not bode well for the lives and fates of more than ten million people and the future trajectory of two nuclear powers who are at daggers drawn, with each nation exhibiting significant International clout. Indians have also been, to some extent, been successful in linking the Kashmiri freedom movement with a broader Islamic terrorism agenda of transnational extremist organizations. This is a significant setback to the Kashmir cause similar to the one in the ‘70s when, after the Simla agreement, the international community viewed both sides as agreeing to manage it as a bilateral dispute. However, the seemingly dormant Kashmir conflict flared back into global powers’ attention after the South Asian nuclear tests of May 1998 and the subsequent Kargil conflict that ensued. The international community took cognizance of the matter as the two rivals detonated atomic weapons within the span of one month. Internationally, the Kashmir dispute was highlighted as one that could lead to a possible nuclear exchange during the Kargil conflict, thus stoking global powers’ attention. However, Indian obduracy prevailed under mounting international pressure-particularly post-Kargil conflict- to reach a durable settlement. Thereafter, the focus on the dispute once again proved to be fleeting.

Kashmiris should not only be taken as images of unfairness: they are genuine individuals carrying on lives in horrendous torment. They have rights under International law, rights which are in essence easily disregarded. Regardless of how the regional issue of Kashmir is settled in the long run, there is a human aspect to Kashmir. This isn’t only a dry lawful question to be bantered in course readings and workshops. The Indian government’s recent legislation regarding changing the domicile law and repealing the special status of the region indicates ulterior motives of the present Bhartiya Janta Party (B.J.P.) government to irreversibly alter the demographics of the only Muslim-majority in the Indian Union. In theory, India could argue that Kashmir is not an “armed conflict” of the type to which war laws apply. However, that debate misses the point: what India has deliberately and consciously adopted as a state policy in Kashmir is so cruel and so inhumane that it would constitute a war crime even if that type of armed conflict existed in the region.

India’s stubbornness in keeping the Kashmir dispute a bilateral matter and in recent times, turning it into a unilateral one creates hindrances for the international community to proactively take up the dispute. Indian government attempts to shift the global attention to terrorism whenever the Pakistani diplomatic corps tries to raise the issue at the global stage. However, linking a legitimate movement for self-determination to terrorism can not go on for so long. In time, Kashmiris’ rightful struggle for self-determination will continue while the terrorism narrative by India and its proxies (as exposed by EU DisInfoLabs) will die down. Suppose we decipher India’s contention that it exercises undisputed sovereignty over Kashmir. In that case, it follows that Kashmiris are entitled to the full range of human rights afforded to them under international law (including the right not to be shot at random with pellet guns [read:shotguns]).

International human rights law on policing and the use of lethal weapons is articulated most plainly in two documents approved by the U.N. General Assembly, i.e., the Code of Conduct for Law Enforcement Officials (1973) and the Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials (1990). Each of these is now regarded as declaratory of the customary law. According to Feisal H.N, writing for TRT world, “The content of these two documents amounts to basic common sense: that the use of force should be limited to the extent necessary, that it should not be disproportionate, that it should be backed by law and that there should be an effective means of accountability if this force is used.”(xvi) However, the way that the territory of Kashmir is disputed has nothing to do with the undisputed human rights of Kashmiris. What is essential is that it is time that the global powers stop choosing to disregard Indian state’s infringement of those rights.

In conclusion, it can be stated that there is no easy road out of this dispute. However, the two sides need to get the assistance of international experts who carve out an unbiased assessment while taking into consideration the historical nuances surrounding the dispute. International conventions and agreements regarding self-determination form the bedrock upon which this conundrum ought to be solved. Mediation efforts involving the good offices’ of global powers should be utilized in order to reach a bilateral settlement. Experts and analysts often ponder whether the Kashmir dispute would still have consumed the time, resources, and attention of the two poverty-stricken South Asian neighbours had the British decisively resolved the territorial dispute between India and Pakistan?[xvii] If the answer is not in the affirmative, then it creates a definite legal and historical obligation on world powers and multilateral institutions to bring forward their expertise and resources to undertake the arduous work required to resolve this seemingly perennial dispute. The Kashmir conundrum has consumed endless human lives from both sides, and a perpetual state of suffering exists in the highly-militarised occupied state. Probably, the time has come that the international powers and key world players should give up their hypocrisy and abandon their dual standards towards this very real and burning issue. On the other hand, the clock is already ticking and it may lead into an armed conflict between the two arch rivals any time..

References

[i] Brian Farrell, “The Role of International Law in the Kashmir Conflict,” Penn State International Law Review. Vol 24, no 2 (2003), elibrary.law.psu.edu

[ii]Choudhary (ed.), supra note 14, vol. 15, at p. 370. See further, “Memorandum on the Kashmir Reference to the U.N.O. – Historical Background”. Choudhary (ed.), supra note 14, vol. 10, at p. 328.

[iii] Prem Nath Bazaz, Inside Kashmir (Srinagar: Kashmir Pub. Co.,1941), 250

[iv] V.P. Menon, Integration of the Indian States (Hyderabad: Orient Blackswan Pvt. Ltd., 2014), at p. 354.

[v]Chandrachud, Abhinav, The Abrogation of Article 370 (August 24th, 2019). Festschrift in Honour of Nani Palkhivala (January 2020, F), Available at S.S.R.N.: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3448331

[vi] A.G Noorani, ‘Article 370: A Constitutional History of Jammu and Kashmir’ (2011) [Oxford University Press, 2011]

[vii] Civil Appeals Nos. 12237-12238 of 2016.

[viii] Sheikh Muhammad Adnan, STATUS OF KASHMIR UNDER “THE RIGHT OF SELFDETERMINATION WITHIN THE AMBIT OF INTERNATIONAL LAW”, S.S.R.N., July 09th 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3490721

[ix]ibid

[x]Umer Akram Chaudhary, “Article 370’s Hollow Promise” The News, August 18th 2019, thenews.com.pk

[xi] vii

[xii] Howard.B.Schaffer, “The International Community and, Kashmir,” 2008.

[xiii]xii

[xiv]xii

[xvi] Feisal Naqvi, “Kashmir: Turning a blind eye”, TRT World, October 05th 2020, https://www.trtworld.com/

[xvii]Aisha Sultanat, “Internationalizing the Kashmir Dispute”, Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies, July 08th 2002. https://www.ipcs.org