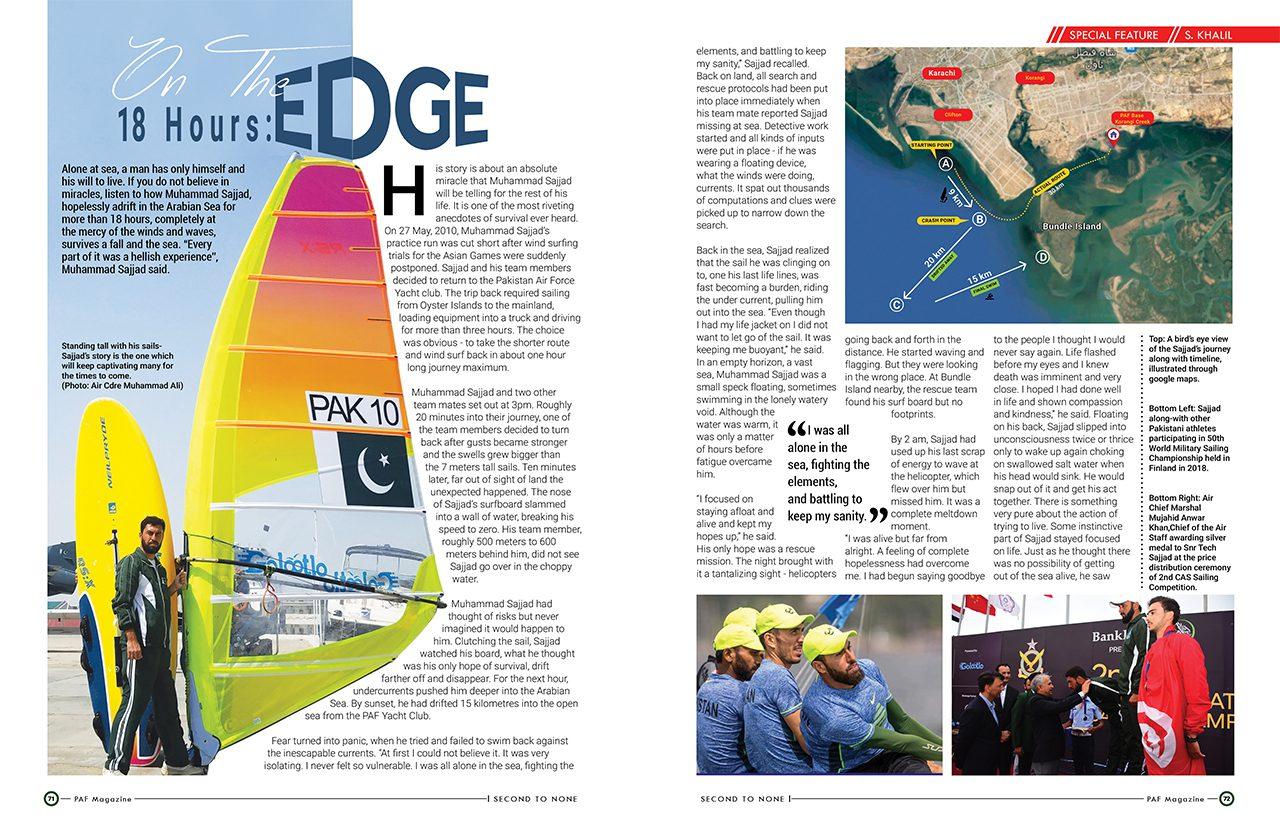

Alone at sea, a man has only himself and his will to live. If you do not believe in miracles, listen to how Muhammad Sajjad, hopelessly adrift in the Arabian Sea for more than 18 hours, completely at the mercy of the winds and waves, survives a fall and the sea. “Every part of it was a hellish experience”, Muhammad Sajjad said.

His story is about an absolute miracle that Muhammad Sajjad will be telling for the rest of his life. It is one of the most riveting anecdotes of survival ever heard. On 27 May, 2010, Muhammad Sajjad’s practice run was cut short after wind surfing trials for the Asian Games were suddenly postponed. Sajjad and his team members decided to return to the Pakistan Air Force Yacht club. The trip back required sailing from Oyster Islands to the mainland, loading equipment into a truck and driving for more than three hours. The choice was obvious – to take the shorter route and wind surf back in about one hour long journey maximum.

Muhammad Sajjad and two other team mates set out at 3pm. Roughly 20 minutes into their journey, one of the team members decided to turn back after gusts became stronger and the swells grew bigger than the 7 meters tall sails. Ten minutes later, far out of sight of land the unexpected happened. The nose of Sajjad’s surfboard slammed into a wall of water, breaking his speed to zero. His team member, roughly 500 meters to 600 meters behind him, did not see Sajjad go over in the choppy water.

Muhammad Sajjad had thought of risks but never imagined it would happen to him. Clutching the sail, Sajjad watched his board, what he thought was his only hope of survival, drift farther off and disappear. For the next hour, undercurrents pushed him deeper into the Arabian Sea. By sunset, he had drifted 15 kilometres into the open sea from the PAF Yacht Club.

Fear turned into panic, when he tried and failed to swim back against the inescapable currents. “At first I could not believe it. It was very isolating. I never felt so vulnerable. I was all alone in the sea, fighting the elements, and battling to keep my sanity,” Sajjad recalled. Back on land, all search and rescue protocols had been put into place immediately when his team mate reported Sajjad missing at sea. Detective work started and all kinds of inputs were put in place – if he was wearing a floating device, what the winds were doing, currents. It spat out thousands of computations and clues were picked up to narrow down the search.

Back in the sea, Sajjad realized that the sail he was clinging on to, one his last life lines, was fast becoming a burden, riding the under current, pulling him out into the sea. “Even though I had my life jacket on I did not want to let go of the sail. It was keeping me buoyant,” he said. In an empty horizon, a vast sea, Muhammad Sajjad was a small speck floating, sometimes swimming in the lonely watery void. Although the water was warm, it was only a matter of hours before fatigue overcame him.

“I focused on staying afloat and alive and kept my hopes up,” he said. His only hope was a rescue mission. The night brought with it a tantalizing sight – helicopters going back and forth in the distance. He started waving and flagging. But they were looking in the wrong place. At Bundle Island nearby, the rescue team found his surf board but no footprints.

By 2 am, Sajjad had used up his last scrap of energy to wave at the helicopter, which flew over him but missed him. It was a complete meltdown moment.

“I was alive but far from alright. A feeling of complete hopelessness had overcome me. I had begun saying goodbye to the people I thought I would never say again. Life flashed before my eyes and I knew death was imminent and very close. I hoped I had done well in life and shown compassion and kindness,” he said. Floating on his back, Sajjad slipped into unconsciousness twice or thrice only to wake up again choking on swallowed salt water when his head would sink. He would snap out of it and get his act together. There is something very pure about the action of trying to live. Some instinctive part of Sajjad stayed focused on life. Just as he thought there was no possibility of getting out of the sea alive, he saw silhouettes of trees spaced across the land. It was a lucky break since his ordeal began. Drawing on emergency reserves of adrenaline, he started swimming slowly, calmly and collected. Until he felt land, in waist deep water. He could stand. The next 100 meters or so he took every step carefully fearing not might plunge into a drop. He made it to the remote and desolate Bundle Island by 6am. His clothes and the life jacket had cut into his skin around his neck and in his armpits. He was ravaged with hunger, dehydrated and his body desperately weak. At the risk of being eaten alive by stray dogs, Sajjad decided not to get a shut eye. “Physiologically and mentally I was done. I was in no physical condition for a prolonged wait and I had accepted that I was completely on my own and took survival into my own hands. By daybreak I could see the Oyster Islands 5 kilometres away. Against every instinct, I went back into the water. I figured the waves would carry me,” he said.

Surrounded by the immensity of the Arabian Sea, and just when his mind was once again about to be consumed by that horrific feeling of isolation, Sajjad was spotted by fishermen. “They asked me what I was doing in the water this early. I told them I had been lost at sea the entire night,” Sajjad said.

At the PAF base, the signal for casualty was out. A cheque for compensation money had been written. It was only a matter of time when it would be announced officially. But it was sheer elation when he walked in at his own funeral preparations.

“I had everything to live for, my parents, my siblings and my fiance. I had a chance at life and I decided to fight for it,” he said.

Muhammad Sajjad returned to windsurfing, in the very waters that nearly took his life..