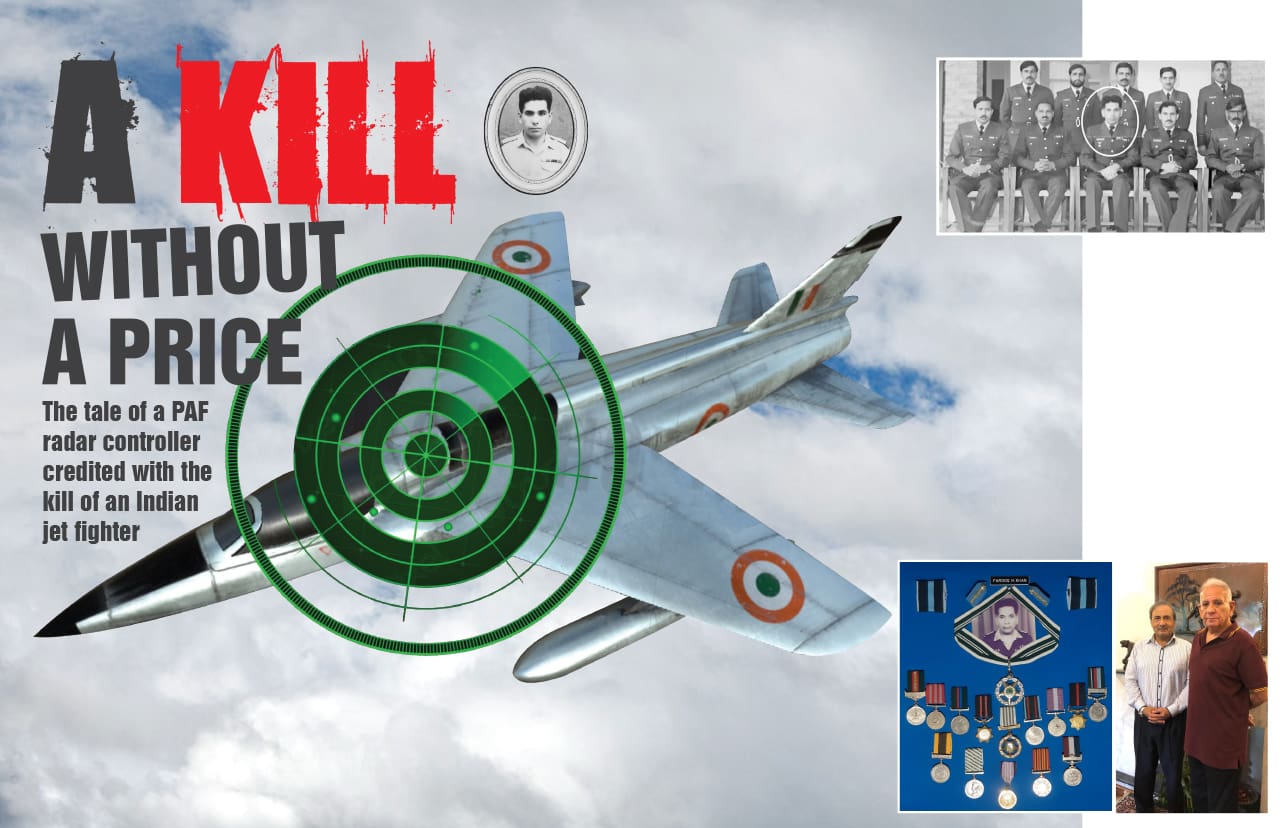

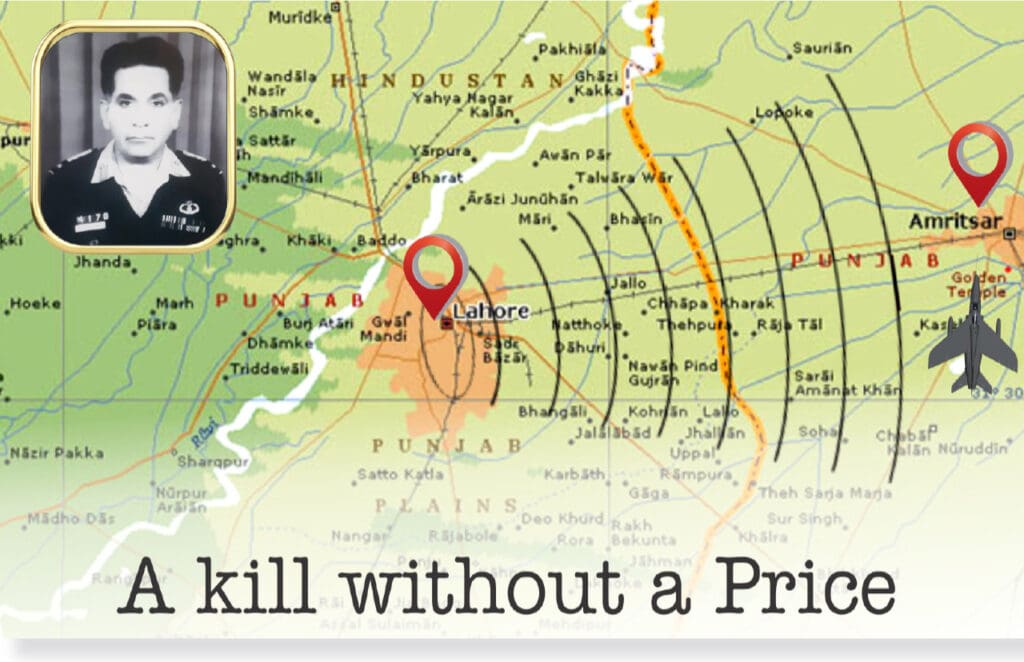

The tale of a PAF radar controller credited with the kill of an Indian jet fighter

In a remarkable display of ingenuity and resourcefulness, a PAF Air Defence Controller showcased exceptional out-of-the-box thinking while sitting behind his radar screen near Lahore. This gripping account highlights how his quick wits, innovative approach, and remarkable ability to adapt and improvise, led him to down an Indian Air Force jet across the border, proving that intelligence and creativity can be as mighty as any weapon on the battlefield.

War is an armed conflict between two or more rival groups. It has existed since time immemorial. In the recorded history of the last 5000 years, mankind has witnessed all kinds of wars and battles of varying magnitudes and scales in different parts of the world. Wars have been waged for different reasons and motives, including competition to occupy lands, hegemonic designs, religious conflicts, and nationalism. Imperialism, racism, and slavery have also caused armed conflicts in different periods of history. During hostilities, depending on the nature of the conflict, all possible military resources are employed to inflict military, economic, and social damage on the enemy. The grand objective is to force the enemy to capitulate, thus enabling the winner or the dominating side to gain a psychological and moral advantage during the post-war negotiations. That is why everything is said to be fair in war and love, and every effort is made to cause the enemy irreparable loss through all possible means and methods as well as by exploiting every opportunity.

If we look at the effectiveness and efficacy of combat operations of Pakistan Air Force during the 1965 and 1971 wars, it will be abundantly clear that the pilots, engineers, air defence controllers, air traffic controllers, technicians and civilians of the nation’s arms have always performed exceedingly well. Unfortunately, in the 1971 war, Pakistan lost its Eastern wing. In the aftermath of the lost war, many valiant warriors who had displayed unparalleled bravery and patriotism were relegated to the obscurity of unsung heroes. Generally, when we talk about victories in the air, only the heroic tales of pilots flash into our minds, because primarily it is they who go into action and inflict losses on the enemy within their own country’s air space as well as inside the enemy territory. What is most amazing and riveting is the story of a war hero sitting on the ground, across the radar screen with no weapons. Yet, he destroyed neatly an enemy fighter jet.

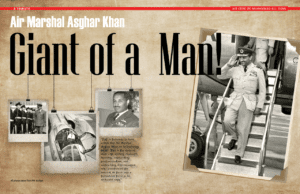

Air Commodore Farooq Haider (R) is adored as an ace radar controller of the 1965 and 1971 wars. Narrating his feat of courage and professional brilliance, the famed veteran and war hero of Pakistan Air Force, Air Commodore Sajjad Haider (R) says: “Farooq Haider was one of the best Air Defence Controllers who possessed a very calm but timely judgment and commanding voice”. It must be kept in mind that in the 60s and 70s, fighter jets were either without airborne radars or had very limited range. As such, the role of the ground controller to find out the enemy’s position, direction, and relative distance was very critical for the combat pilots.

Primarily inducted into the GD Pilot Branch, whilst undergoing training at PAF Academy, Farooq was selected for training at the US Air Force Academy. As ill luck would have it, due to heart murmurs, he was absorbed into the Air Defence branch. Air Defence officers use radar from the ground to guide fighter pilots and inform their own aircraft about the presence and location of enemy planes in a timely manner.

Flight Lieutenant at that time (later retired as Air Commodore) Farooq carried out numerous radar control missions in the 1965 war and acquitted himself as a highly reliable and proficient radar controller.

Just before the outbreak of the 1965 war, on 1st September 1965, PAF scored its first victory when Squadron Leader Sarfraz Rafiqui and Flight Lieutenant Imtiaz Bhatti shot down Indian Vampires, two each, in Chamb sector while these were attacking Pakistani troops. Rafiqui closed in fast and shot down two Vampires and then, like a great leader and skilled pilot, he let his No.2, Bhatti, prove his mettle and he also claimed two Vampires. All the Vampires were downed in full view of the baffled Indian troops. The IAF was hugely devastated and withdrew immediately about 130 Vampires and over 50 Ouragons from the war theatre which means 35% of IAF was grounded in a single mission. On the ground, sitting on radar scope, Farooq Haider accomplished a singular feat by vectoring timely and accurately the PAF jets to the target area.

In another pre-war mission on September 3, 1965, Squadron Leader Yousuf, strapped in an F-86, singly faced six Indian aircraft. Later, Flying Officer Abbas Mirza (retired as Air Vice Marshal) to provide support with his F-104 Starfighter. It was during the same mission that an Indian Gnat aircraft had to force-land at Pasrur (Pakistan). Flt. Lt. Farooq Haider was yet again the controller of this memorable mission.

The real axis in the 1971 war was East Pakistan. During this conflict, as a part of its defence strategy, Pakistan Air Force had to operate cautiously in order to preserve its assets and effort. This was done considering the possibility of launching a major attack against India from West Pakistan and the eventuality of providing full air support for the ground forces to succeed. It was a painful situation for the pilots and the controllers of the Pakistan Air Force in West Pakistan, who were fully poised to challenge the Indian Air Force fighter jets which were violating brazenly Pakistan’s airspace. The air defence controllers in the West were confident that if allowed to intercept these intruders, they would make sure to decimate the majority of Indian aircraft. During an exclusive interview with the author, recalling his war experience fifty years ago, Air Commodore Farooq Haider (R) reminisced, “One day sitting idle on the radar scope I was feeling bored as there was nothing to do. I spotted a blip on my radar screen. This was inside the Indian border near a place called Patti on the main road south of Amritsar (India). The aircraft was heading towards Amritsar.

To kill monotony, a strange idea flashed in my mind, and I decided to intercept the enemy fighter jet without any real fighter interceptor force with me at that moment. So, I picked up the microphone and began talking to an imaginary PAF interceptor formation in the air. While communicating instructions to our fighter jets’(imaginary), I told them NOT to respond to my radio calls. I knew that my radio communication was being monitored by Indian radar controllers. To make the enemy gather from my radio transmission through interception that I had the real jet fighters in the air, I continued urging our ‘fighter jets’ not to respond to my instructions on the radio. I kept conveying the actual position of the enemy aircraft. I believed that when the Indian radar controllers realised that I was accurately reporting the position of the Indian jet fighter, they would trust that my interceptor force was real. Throughout this fake interception, obviously, there was no acknowledgement from our ‘fighter aircraft’. In order to convince the Indian controller that my interceptors were in close proximity to their jet, I kept reminding our pilots not to acknowledge my radio calls. As soon as my ‘fighter jets’ closed on to the enemy jet fighter, the range became lesser and lesser and the angle of attack became favourable.

The enemy aircraft was flying low level so I adjusted the altitude of ‘my fighter jets’. When the range became gradually very close, I directed ‘my fighter jets’ to shoot the enemy and exit the area maintaining a low altitude without announcing on radio outcome of the shooting. “They” were instructed to share the result only after landing. On return of ‘my fighter interceptor’ I monitored the Indian jet a little north of Amritsar, close to the IAF base, located along the northern side of Amritsar city. After a while, it disappeared from my radar screen. I as well as my colleagues had no idea about this aircraft and thought it had finally landed.”

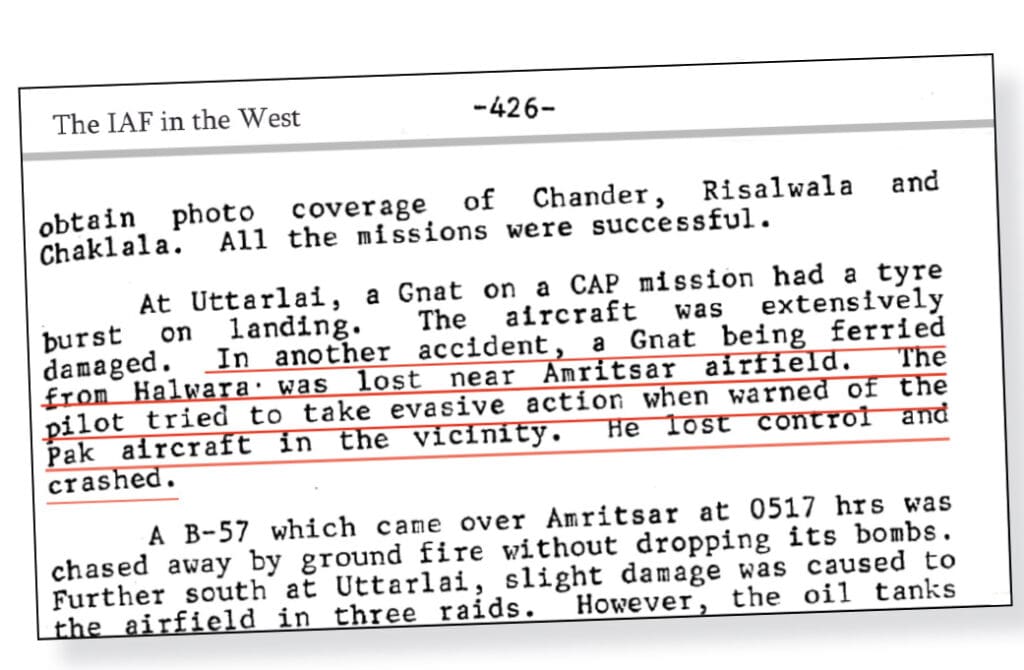

For Air Defence Controllers, the most credible source to ascertain the result of a combat mission is to have their own fighter pilots reporting the outcome of a battle. It is the pilot who can see the enemy aircraft till the last moment and is in a better position to confirm whether the target aircraft was destroyed or it had managed to escape unscathed. But in this case, there was not a single Pakistan Air Force jet in the area. Even years after the end of the war, Sqn Ldr Farooq Haider and his comrades had no knowledge of whether the aircraft had crashed or landed safely. Three decades after the end of the conflict, the war data was officially compiled and documented in the shape of a diary called “ IAF in the West.” The war diary included numerous factors like air raids, aerial kills, victories, and the details of own losses in comparison with the enemy. By looking at this diary critically ( examining specifically chapter 10, page 427), one can establish conclusively that the IAF Indian Gnat aircraft crashed on December 7, 1971, at the same time and place. The record states: “In another accident, a Gnat being ferried from Halwara was lost near Amritsar airfield. The pilot tried to take evasive action when warned of the Pak aircraft in the vicinity. He lost control and crashed”. The only fact missing in the whole text is the falsely believed presence of Pakistan Air Force fighter jets in the area. Sqn Ldr Farooq Haider accomplished the rare feat of destroying the enemy aircraft, using a unique air warfare tactic: applying his extraordinary mental and professional skills. This was most incredible because never in the history of air warfare was such a prank taught or discussed in books. Slaying an enemy aircraft without engaging its own jets, without expending even a single litre of gasoline and firing a bullet is hitherto a nonpareil feat. It can be rightly described as a ‘kill without a price’. Farooq Haider deserves a standing ovation for making this happen. Sadly, it took an enormously long time to find out from across the border the success of this unprecedented mission. For lack of conclusive evidence over a span of half a century, the PAF and the Nation couldn’t commemorate and celebrate Farooq’s marvellous achievement as it deserved.

For an honourable air defence controller infused with deep patriotic passion- the like of Farooq Haider- there is always abundant solace in being once part of an epic air campaign and being honoured (albeit inordinately late) as a war hero who contributed handsomely to PAF’s tally of kills.