Exclusive Report on Iniochos Exercise-2022

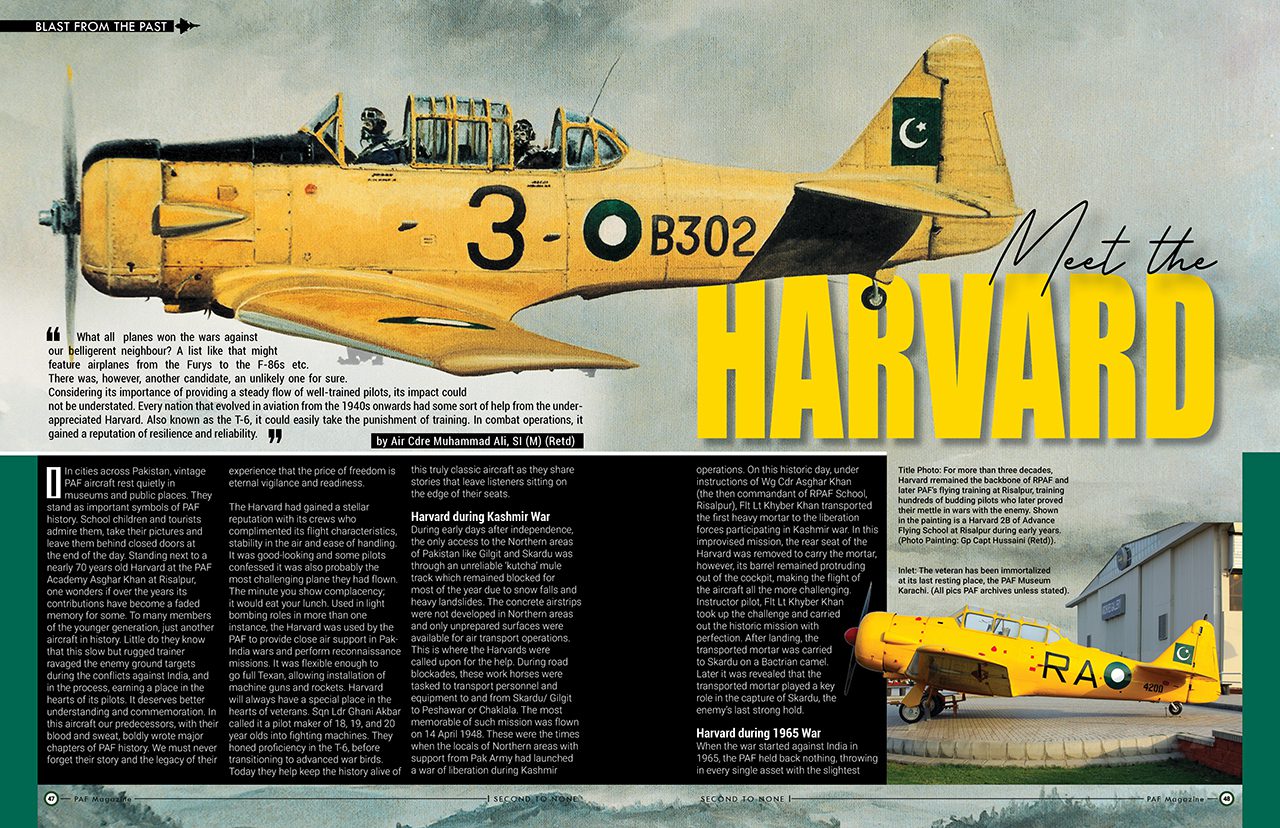

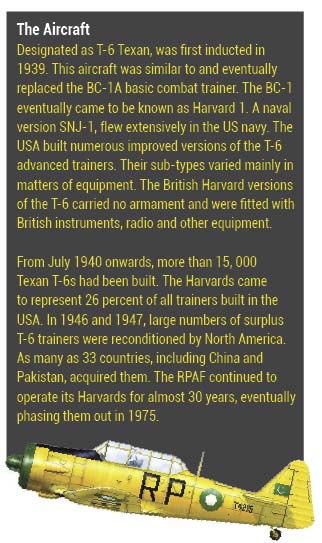

What all planes won the wars against our belligerent neighbour? A list like that might feature airplanes from the Furys to the F-86s etc. There was, however, another candidate, an unlikely one for sure. Considering its importance of providing a steady flow of well-trained pilots, its impact could not be understated. Every nation that evolved in aviation from the 1940s onwards had some sort of help from the under-appreciated Harvard. Also known as the T-6, it could easily take the punishment of training. In combat operations, it gained a reputation of resilience and reliability.

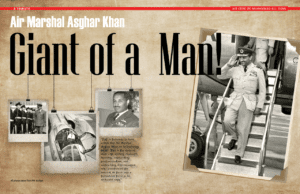

IIn cities across Pakistan, vintage PAF aircraft rest quietly in museums and public places. They stand as important symbols of PAF history. School children and tourists admire them, take their pictures and leave them behind closed doors at the end of the day. Standing next to a nearly 70 years old Harvard at the PAF Academy Asghar Khan at Risalpur, one wonders if over the years its contributions have become a faded memory for some. To many members of the younger generation, just another aircraft in history. Little do they know that this slow but rugged trainer ravaged the enemy ground targets during the conflicts against India, and in the process, earning a place in the hearts of its pilots. It deserves better understanding and commemoration. In this aircraft our predecessors, with their blood and sweat, boldly wrote major chapters of PAF history. We must never forget their story and the legacy of their experience that the price of freedom is eternal vigilance and readiness.

The Harvard had gained a stellar reputation with its crews who complimented its flight characteristics, stability in the air and ease of handling. It was good-looking and some pilots confessed it was also probably the most challenging plane they had flown. The minute you show complacency; it would eat your lunch. Used in light bombing roles in more than one instance, the Harvard was used by the PAF to provide close air support in Pak-India wars and perform reconnaissance missions. It was flexible enough to go full Texan, allowing installation of machine guns and rockets. Harvard will always have a special place in the hearts of veterans. Sqn Ldr Ghani Akbar called it a pilot maker of 18, 19, and 20 year olds into fighting machines. They honed proficiency in the T-6, before transitioning to advanced war birds. Today they help keep the history alive of this truly classic aircraft as they share stories that leave listeners sitting on the edge of their seats.

Harvard during Kashmir War

During early days after independence, the only access to the Northern areas of Pakistan like Gilgit and Skardu was through an unreliable ‘kutcha’ mule track which remained blocked for most of the year due to snow falls and heavy landslides. The concrete airstrips were not developed in Northern areas and only unprepared surfaces were available for air transport operations. This is where the Harvards were called upon for the help. During road blockades, these work horses were tasked to transport personnel and equipment to and from Skardu/ Gilgit to Peshawar or Chaklala. The most memorable of such mission was flown on 14 April 1948. These were the times when the locals of Northern areas with support from Pak Army had launched a war of liberation during Kashmir operations. On this historic day, under instructions of Wg Cdr Asghar Khan (the then commandant of RPAF School, Risalpur), Flt Lt Khyber Khan transported the first heavy mortar to the liberation forces participating in Kashmir war. In this improvised mission, the rear seat of the Harvard was removed to carry the mortar, however, its barrel remained protruding out of the cockpit, making the flight of the aircraft all the more challenging. Instructor pilot, Flt Lt Khyber Khan took up the challenge and carried out the historic mission with perfection. After landing, the transported mortar was carried to Skardu on a Bactrian camel. Later it was revealed that the transported mortar played a key role in the capture of Skardu, the enemy’s last strong hold.

Harvard during 1965 War

When the war started against India in 1965, the PAF held back nothing, throwing in every single asset with the slightest destructive power needed to wreak havoc on the enemy. Coming in on a fast dive, Harvards could inflict their firepower on the ground targets and make good its escape before enemy fighters had a chance to intercept, making panicked infantry men running for their lives.

During the war, seven Harvards were earmarked for the first night’s mission. Since the Harvards operated from Risalpur, the air staff directed to use PAF Base Chaklala at Rawalpindi, as their refuelling station and final jumping board for operations. From Chaklala, each sortie was planned for about three hours and ten minutes. Pilots stretched the Harvard to the limits of its fuel endurance.

On 6 September, all seven Harvards topped up at Chaklala for a search, to locate and engage enemy troop concentrations and movements on the Amritsar-Jullundur Road. Four aircraft were to prowl along the road to Jullundur, while the rest would scout other stretches. Taking off from Chaklala after dark, the Harvards set out on their individual missions at intervals. Flying over the hills, pilots descended to roughly 500 feet after crossing Chenab River. They risked themselves being shot down by friend and foe alike, as they flew within the reach of even the small arms fire.

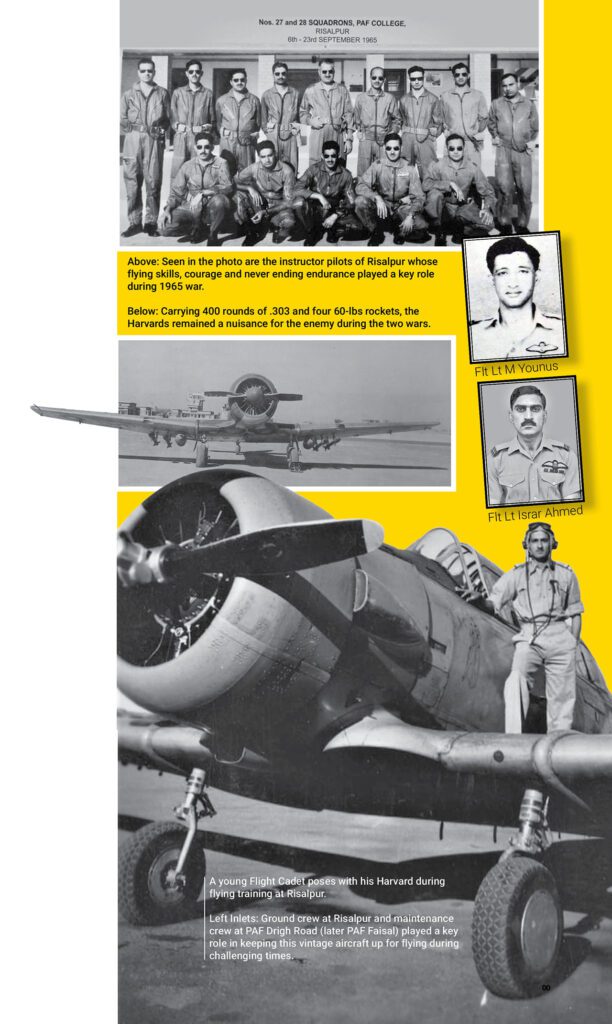

Flt Lt M Younus, who flew four such missions, aptly portrayed in one of his debriefs, the devil-may-care spirit in which they were undertaken. “My first mission was on the Amritsar-Pathankot sector on the night of 6 September. Flying at about 300 to 400 feet above ground level (AGL), I headed for Lahore and noticed en route that Mangla dam area was lit like a Christmas tree.

Next, I saw an almost continuous mosaic of flashes and tracers in the battle areas southwards from Jhelum and this got the adrenaline going. My canopy was open against the humid head wind of September and I was even able to pick up the odour of burnt cordite hanging in the air. I noticed some light arms fire coming up near Dhariwal. I fired off some rounds of my two guns, which generated a small explosion in the target area – probably a fuel truck. At the end of my leg, I let go my rockets at a small bridge but I doubt that they connected.”

On that first night, pilots harassed an enemy convoy along the Batala-Chhina Road, dodging the enemy ack-ack, escaping without any damage. There was a warmer welcome from enemy ack-ack on the Harvards, ten miles northeast of Amritsar, but again no one was hit. On the Gurdaspur-Amritsar and Amritsar-Pathankot roads, PAF pilots located more Indian troop concentrations, attacking them on the road bridge over the canal of Deena Nagar. Such attacks in themselves could not do any serious damage, but they were to prove successful in deterring enemy road and rail movements on the Amritsar-Pathankot Road.

On completion of their mission, and as they reached Chaklala, the airfield came under attack by enemy fighters. As five aircraft had already returned to Risalpur via Chaklala, two Harvards were rerouted to Sargodha, dangerously low on fuel. Worst, light ack-ack opened up over Rawalpindi to deter the invading Indian Canberras. Groping their way around in the dark, the two Harvards were fortunate to reach safety, one at Sargodha, the other at Risalpur, to which the pilots had decided to divert.

Harvard during 1971 War

Once again during 1971 War, the instructor pilots at Risalpur were called upon to replicate the heroics of 1965 war. Several night flying sorties were carried out by these dare-devil instructor pilots. However, one important sortie needs a special mention. On the night of 5 Dec 1971, when the war was hardly 24 hours old, Flt Lt Israr Ahmed (instructor pilot of Harvard at Risalpur) was tasked to fly a vital interdiction mission in Chamb-Akhnur area where the two armies were fighting a stiff battle. Pak Army needed close support and convoy interdiction missions at regular intervals. On that day, Flt Lt Israr Ahmed took off in pitch-dark night and landed at Chaklala for refuelling. With fuel tanks fully topped up, Flt Lt Israr took off for the daring mission. Flying low, he reached the area with pinpoint accuracy. As he pulled-up for the first attack on the convoy, the enemy ack-ack gave him a hot reception. Undaunted he pressed on and attacked the target. As he pulled-up for exit, his T-6 G Harvard was hit by the enemy ground fire and a shell fractured his right arm. Profusely bleeding, he flew the aircraft with determination. Kissing the curvature of the earth, he exited the battle area and later climbed to higher level, and headed home. He flew the aircraft meticulously and landed back safely at base. The great heroics done by resilient Israr not only saved the valuable aircraft but also became the symbol of pride for all the flying instructors of Risalpur. Flt Lt Israr valour earned him Sitar-e-Jurat during 1965, first ever for an instructor pilot and that too on a vintage Harvard aircraft.

The Training

The Harvard was the most significant training aircraft and those privileged to fly one testified that there wasn’t anyone who did not love the Harvard. As an advanced trainer, the T-6 was a lot of students’ first introduction to more complex aircraft systems, remembering the propeller nomenclature, and learning landing gear speeds etc. There was something mystical about flying an airplane designed to fly like a fighter. The T-6 was an airplane that had to be mastered before a military pilot could solo a really fire breathing war bird. “It was a much more responsive airplane than a pilot expected. Flying a Harvard was the closest most pilots came to flying a mustang or a hurricane,” Sqn Ldr Ghani Akbar (Retd), SJ of 1965 war, said.

The veteran described the classical airplane, a pre-WWII design, highly manoeuvrable that could do all sorts of aerobatics. Even though the T-6 was the best trainer of the time, it was not easy to fly. “One could see the real worth of the person in a Harvard aircraft and many did not make it. As wonderful as it was to fly, a pilot’s biggest test was to land this tail dragger. The trick to land safely was the three-pointer landing, with all three wheels contacting the ground at the same time while holding the attitude to prevent the tail from swinging. Landing on front two gears was risky at 55 knots. Many pilots got suspended,” Sqn Ldr Ghani Akbar (Retd) said, who also later became an instructor on the Harvard aircraft.

Nothing was startling about the performance of a Harvard, and the thrill of flying this machine was visceral, like flying into battle. In February 1960, Ghani Akbar was into his second solo, when, surprisingly the engine packed up. “When it did not start, I focused on forced landing. Found a strip near a field for a belly landing. Farmers in the field didn’t scatter until touch down. They thought it was just a routine practice approach which the student pilots used to carry out every day. The plane was flying again after two days,” he said quipping.

AVM Hamid Khawaja (Retd), an instructor on Harvard in 1974, who trained pilots going on to the fighters, is also one of the many admirers of the Harvard. “It was a very powerful aircraft, you just ram the throttle and the aircraft would respond instantaneously,” said AVM Hamid Khawaja (Retd), a 1,000 hours Texan pilot without a single incident of swing. “You can do any type of aerobatics on the Harvard, be it a slow roll or a roll of the top. The aircraft always responded well thanks to its herculean engine power,” said AVM Hamid Khawaja (Retd).

Although he described the T-6 as reliable and one that would easily recover from a spin, the aircraft could not be taken for granted. “Out of all the various flying phases of training, doing instrument flying on Harvards was much challenging especially if you were a student. It hardly had any reliable instruments, the gyros were highly unreliable and would topple after mere 30 degrees of turn,” the veteran said, who nonetheless preferred Harvard for almost any kind of aerobatics. “Taxi was another difficult task on Harvard, being the instructor sitting in the rear seat you could not see anything in front to remain on yellow line. You have to rely on the student during taxi and that was a tricky part. You never taxi straight in a Harvard, you move the aircraft in zig-zag to clear the area on all sides to avoid obstacles or other aircraft,” added AVM Hamid Khawaja (Retd).

Harvard- Over the Years

At the time of partition, the RPAF received a mix of 20 Harvard 2Bs and 2Cs. With such few aircraft, the PAF made further purchases of T-6s from the USA and Canada. On 6 September 1947, instructor pilots Sqn Ldrs Khyber Khan, SA Aziz and Flt Lts Rahim Khan and Zafar Chaudhry and two cadet pilots, flew the first contingent of training aircraft into Pakistan. These were the six Harvard 2Bs from Ambala. During landing a cadet scraped a wing tip on the runway. It was Risalpur’s first minor accident. Next day, the aircraft were painted in the new PAF markings, which swept an excitement through Risalpur.

By October 1947, the high command had established three small training units at Risalpur. Four Tiger Moths made up the elementary flying training squadron. The advanced flying training squadron consisted of four Harvard 2Bs and a flight of two Harvard 2Cs for squadron training. The total of two flights seemed meagre today but, at that time, it was equal to almost half of all the other aircraft possessed by the RPAF.

As Indian threats grew along Pakistan’s borders, flying training was placed on a war footing. The duration of the course was halved from 18 to nine months. The RPAF acquired 14 Tiger Moths, and 30 Harvards T-6Gs were bought from the USA, but took over a year to be delivered. The first batch was not inducted until March 49. These T-6Gs were better at controls, especially with a tailwheel locking mechanism, significantly reducing swinging on landing, which had plagued Risalpur. By 1960, the RPAF replaced the oldest Harvards, with another ten from the USA.

The Harvard 2Bs and 2Cs remained in service until they were withdrawn in August 1962, after providing 15 years of invaluable training right from Risalpur’s embryonic stage to serving as a vital communication link to Gilgit during the 1948, Kashmir operations. Nonetheless, until 1975, the T-6Gs provided excellent basic flying training to a majority of PAF pilots. During the 1965 war, instructors from the Flying Instructors’ School (FIS) at Risalpur, armed these piston engine trainers, with two .303 Browning machine guns and four rockets each, to harass forward Indian positions in moonlit nights.

Showing the Flag

The first ever military parade in Pakistan was held on 16 August, 1947. PAF’s participation was limited to a fly past by four Tempest aircraft. Two years later, fly pasts were different. Flt Lt MA Rabbani (who later retd as Gp Capt), was tasked to fly a contingent of Harvards from Risalpur to Masroor for participation in Independence Day celebrations. Odds were stacked up against such an operation. Ground crew endeavoured to make 21 Harvards fit and fly worthy, including the one declassed to be cannibalized. The unpredictable monsoon weather made flying risky. Nonetheless, on 9 August, 1949, 21 Harvards from Risalpur, formed five sets of diamonds of four planes each and set course for Multan. It was the first time that Risalpur saw so many Harvard planes together in the sky. “It must have been a sight to watch,” remembered Gp Capt MA Rabbani in his book “My Years in Blue Uniform”. Two hours later, bad weather forced the formation to abort the mission and return to Risalpur. After refuelling, the 21 aircraft took off from home base and headed to Multan again. At Multan they were to be refuelled, take-off and make a pit stop at Hyderabad, to top up again and carry on to their final destination. Sometime into the journey, team leader Flt Lt MA Rabbani was forced to return to Risalpur after his plane developed technical faults. He joined his team in Multan around dusk.

Before continuing, Flt Lt MA Rabbani was directed to refuel at Hyderabad, against his repeated requests to make refuelling arrangements at Nawabshah instead. “I knew that persistent monsoon would have made the grassy landing strip at Hyderabad muddy and slushy,” he recalled. Soon after the 21 Harvards had taken to the sky for Hyderabad the next morning, MA Rabbani ran into engine trouble again and was forced to land on an abandoned air strip at Sukkar. It took 45 minutes before his ‘fitter’ could fix the plane and get airborne. Short on fuel, MA Rabbani could not have made it to Hyderabad hence decided to land at a partly submerged runway at Nawabshah, only to learn to his horror that the contingent had not arrived at Hyderabad for refuelling.

He was petrified with the thought of 20 Harvards, critically low on fuel, hovering over a slushy air strip of Hyderabad. “Panic overwhelmed some of the pilots, who broke away from the formation in search of a landing strip in case of emergency. One Polish instructor in a Harvard 2C, with longer range, made straight to Mauripur. Sqn Ldr Eric Hall (Staff officer at Masroor) brought the rest of the formation to Bholari (a small airstrip near Hyderabad), with their fuel tanks almost dry,” MA Rabbani wrote in his book.

Flt Lt Rabbani took off again and headed towards the dreaded scene of a possible disaster of 20 Harvards. Flying low above Hyderabad, he could see the muddy landing strip but no Harvards. “As I climbed up and wide out of Hyderabad circuit, I noticed a landing strip and the missing ‘nineteen’ parked neatly in line. I heaved a sigh of relief to join my colleagues for a second time in two days. I led the refuelled Harvards to Mauripur, a one hour run from Bholari,” he added.

The next morning, AVM Atcherley, known for his dominating personality, blasted MA Rabbani off his feet for indiscipline, using vocabulary that would blush anyone. Despite his efforts to explain, AVM Atcherley wouldn’t have it. “After this dressing down, I managed to retain my senses and the fly past rehearsal went well. We finally made it to Pakistan’s first proper Independence Day fly past. It was our moment in the sun. The Harvards were a special attraction, staying in sight longer than the speedier Furies and Tempests.”

“Pretty good performance by your boys, good show,” AVM Atcherley told Flt Lt MA Rabbani when they ran into each other at a reception later that evening. It was a red-letter day for the RPAF too, setting a trend for some remarkable fly-pasts and air displays that the service became famous for.

A year later, in March 1950, Flt Lt MA Rabbani, led his last formation of Harvards for Shahinshah of Iran, during his visit to Risalpu.

It was in Lahore, on 26 February, 1955, when 33 Harvards in immaculate formation spelled the letters ‘RPAF’ over a parade. Later in the display, 27 Harvards formed a crescent and star, the motif on the Pakistani flag.

Not All Pilots had Nine Lives

Today the men and women who proudly wear the uniform remember the airmen and the events of 50 years ago. They salute those who battled bravely in defence of our nation. Returning from time warp and mourning inwardly, AVM Hamid Khawaja (Retd) remembers comrades and friends who crashed in the Harvard. “A pilot crashed after one of the wings blew away during flight, two instructors died after the plane stalled, one student pilot rammed into the propeller of a started-up Harvard and was chopped off and another pilot crashed after getting disoriented,” he remembers with a heavy heart.

Amongst the saddest accidents was the first fatal air crash at Gilgit on 14 February, 1948, when air force friends lost one of their comrades, the young Plt Off Asif Khan. A three-ship formation of Harvard aircraft led by legendary PAF pilot FS Hussain with Flg Off Lanky Ahmed on right wing and Plt Off Asif Khan on the left, took off from Peshawar for Gilgit on that sad day. Plt Off Asif Khan, who was one of Air Marshal Asghar Khan’s brothers, was known for daredevil aerobatics – flying so low over Kabul River that the tips of the propeller almost touched the water. Interestingly, Plt Off Asif Khan was supposed to bring back his elder brother, legendary and famous Maj Aslam Khan (the officer played a key role in liberation of Northern Areas in 1948 and was later awarded with gallantry medals) in the back seat of his Harvard. Sadly that never happened.

Before landing at Gilgit, young Plt Off Asif Khan decided to perform some aerobatics to impress his brother and other dignitaries watching him over at the airport. While performing such dare devil maneuver, Plt Off Asif Khan performed a slow roll over the town, close to the ground from which the aircraft never recovered. The young pilot officer and the airman sitting in the back seat did not make it.

A Tribute

Today various nonprofit organizations in the USA and Canada have restored and fly the sturdy two-seater that helped train thousands of pilots during World War II and the Korean War. Most veterans, including Ghani Akbar, wished that the PAF followed the tradition, to preserve that portion of history. There is a really significant historical connection with the plane. It was the most recognized trainer, that robust engine and the iconic snarl it made, and wings modified for better stall characteristics. Inside, pilots were greeted to clean selection of instruments and easy access to all the controls – switchology laid out ergonomically, incredibly important in trainer aircraft. Flying a tailwheel, made pilots better in almost every quantifiable way.

The Harvard may not have looked like much compared to those much popular warbirds, yet its service and design ensured that pilots were given the exact training they needed before heading into combat. In doing so it might have contributed more as an aircraft than quite a number of other machines. Unlike many of its contemporaries, the Harvard continued in silence past the three wars with India, providing one generation of pilots after another with the fundamentals of flying training, even after jets were introduced.

Today, we find two in the PAF museum Karachi, to educate, inspire and honour the men who maintained and trained in this historic airplane. And when you see it, instead of just walking by, as we do so many times when we see a shinier warbird next to it, take a minute, and have a look at it,

it deserves it…