The Indus Waters Treaty is dubbed one of the most successful transboundary treaties brokered by the World Bank. It has endured perpetual hostility between India and Pakistan, including three border wars. The Treaty notwithstanding, there still exist a number of water disputes between the two major South Asian countries including construction of controversial Wullar Barrage, Kishanganga Power Project and Baglihar Dam. The author discusses these issues with historical background and political context.

Water conflict is an endemic in South Asia. Every country has an outstanding water dispute in the region, except Bhutan. India has the dubious distinction of being at the centre of most these transboundary water issues, having a conflict with each of its neighbours—China, Bhutan, Bangladesh, Nepal and Pakistan. History of water conflict between India and Pakistan dates back to 1948 when India forestalled the flow of water to Punjab. Due to Pakistan’s overwhelming dependence on water flowing from rivers and tributaries emanating in India, it locked the two countries in a serious dispute. Thereafter, the World Bank brokered the Indus Waters Treaty to resolve their perennial water conflict.

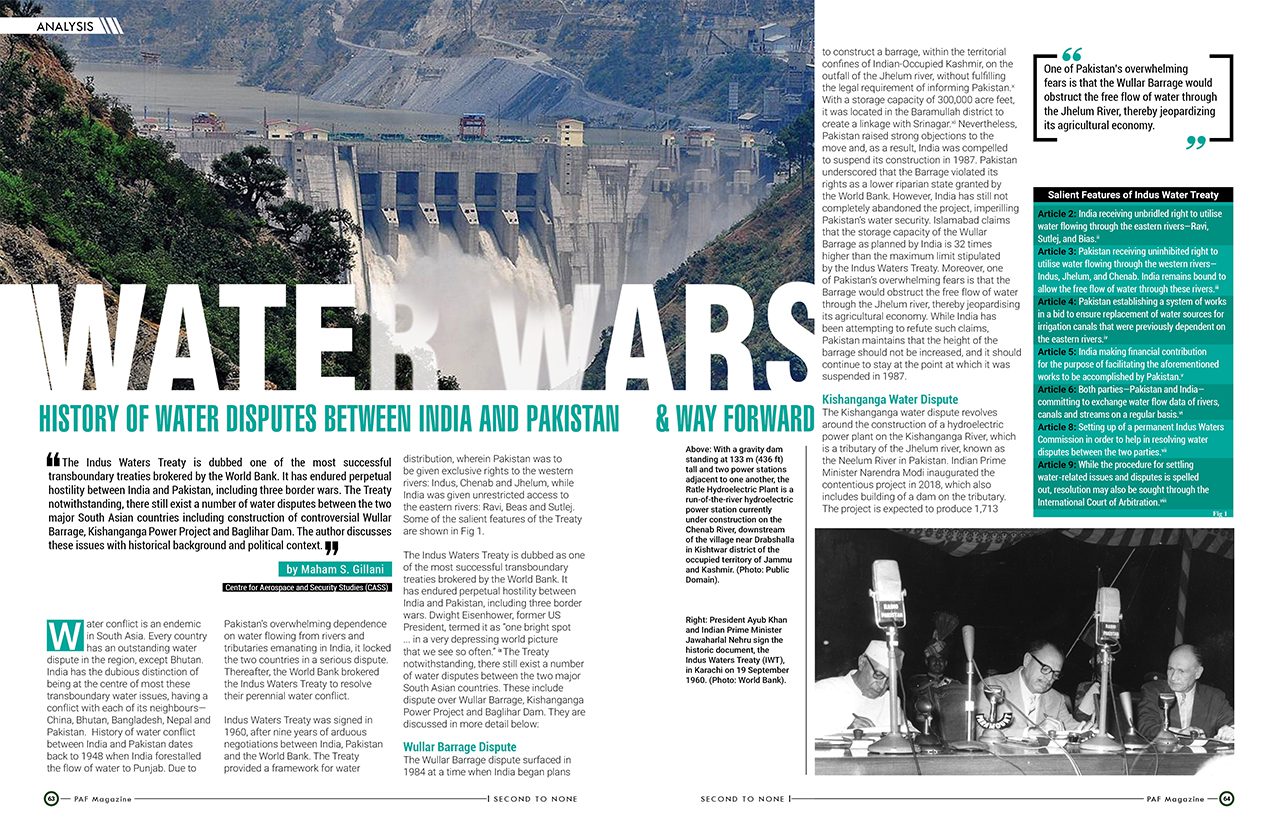

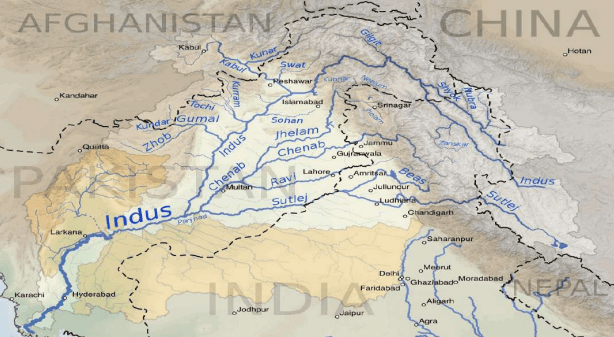

Indus Waters Treaty was signed in 1960, after nine years of arduous negotiations between India, Pakistan and the World Bank. The Treaty provided a framework for water distribution, wherein Pakistan was to be given exclusive rights to the western rivers: Indus, Chenab and Jhelum, while India was given unrestricted access to the eastern rivers: Ravi, Beas and Sutlej. Some of the salient features of the Treaty are shown in Fig 1.

The Indus Waters Treaty is dubbed as one of the most successful transboundary treaties brokered by the World Bank. It has endured perpetual hostility between India and Pakistan, including three border wars. Dwight Eisenhower, former US President, termed it as “one bright spot … in a very depressing world picture that we see so often.” ix The Treaty notwithstanding, there still exist a number of water disputes between the two major South Asian countries. These include dispute over Wullar Barrage, Kishanganga Power Project and Baglihar Dam. They are discussed in more detail below:

Wullar Barrage Dispute

The Wullar Barrage dispute surfaced in 1984 at a time when India began plans to construct a barrage, within the territorial confines of Indian-Occupied Kashmir, on the outfall of the Jhelum river, without fulfilling the legal requirement of informing Pakistan.x With a storage capacity of 300,000 acre feet, it was located in the Baramullah district to create a linkage with Srinagar.xi Nevertheless, Pakistan raised strong objections to the move and, as a result, India was compelled to suspend its construction in 1987. Pakistan underscored that the Barrage violated its rights as a lower riparian state granted by the World Bank. However, India has still not completely abandoned the project, imperilling Pakistan’s water security. Islamabad claims that the storage capacity of the Wullar Barrage as planned by India is 32 times higher than the maximum limit stipulated by the Indus Waters Treaty. Moreover, one of Pakistan’s overwhelming fears is that the Barrage would obstruct the free flow of water through the Jhelum river, thereby jeopardising its agricultural economy. While India has been attempting to refute such claims, Pakistan maintains that the height of the barrage should not be increased, and it should continue to stay at the point at which it was suspended in 1987.

Kishanganga Water Dispute

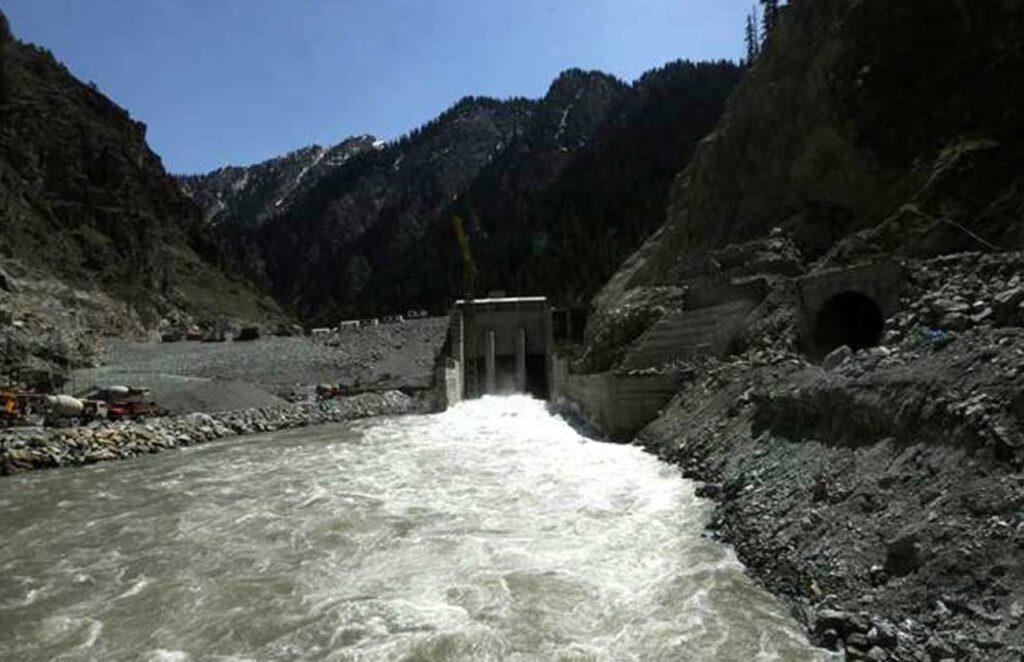

The Kishanganga water dispute revolves around the construction of a hydroelectric power plant on the Kishanganga River, which is a tributary of the Jhelum river, known as the Neelum River in Pakistan. Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the contentious project in 2018, which also includes building of a dam on the tributary. The project is expected to produce 1,713 million units of electricity per year. It is aimed at diverting the water flowing in the Jhelum River towards an underground powerhouse, ultimately making it flow in the opposite direction into Kashmir.xii The Kishanganga (Neelum) River flows through the Neelum Valley located in Azad Kashmir before reaching Gurez—an Indian-occupied region. Therefore, the dam project is geared towards furnishing India with control over a river that flows through Pakistani territory into the Indian-occupied Kashmir before re-entering Pakistan. Pakistan postulates that construction of the hydroelectric power plant on the Neelum River as well as building of the dam is against the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty as it gives Pakistan control of the three western rivers—Indus, Chenab and Jhelum—and India may only use the waters of the rivers thereof in a “non-consumptive” manner.xiii Experts interpret it as a permission to construct “run-of-the-river” hydel projects that by no means change the course of the river or deplete the level of water flowing downstream. Islamabad argues that the power project violates both the conditions set forth in the Indus Waters Treaty by changing the course of the river and also diminishing the level of water flowing downstream.

Baglihar Dam Dispute

India erected the Baglihar Dam—part of a hydroelectricity project—on the Chenab River in the Ramban district of Indian Occupied Kashmir. Islamabad has been raising objections to the project since 1999 when India announced changes to the project design; however, the dam was made operational in 2008. India raised the Dam’s hydro-electricity output to 450 megawatts. Pakistan claims that the new design allows India to potentially inflict colossal damage on it by storing water from the river during the dry season or in the event of a conflict. It could possibly create conditions of drought or flooding in Pakistan.xiv The dispute was ultimately referred to the World Bank, and in 2011 Professor Raymond Lafitte, a neutral expert appointed by the World Bank, announced his final and binding ruling in the case. Interestingly, both the countries hailed the verdict. Although several specifications contested by Pakistan were addressed, the overall design of the dam was left intact. Pakistan believes that the minor changes in design parameters will not make a considerable difference to the initial design.

Implications for Pakistan

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has reported that Pakistan is one of the most water stressed countries in the world. (Fig 2) The Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR) has also warned that Pakistan could run out of water by 2025 if efficacious measures are not taken by the government. In this context, water conflict with India poses staggering challenges for the country.

Pakistan is worried that the Indian projects would substantially decrease the amount of water for its agricultural, industrial and domestic use. Rendering the matter more intractable is the fact that India’s capacity to store and release Pakistan’s water resources at will could invariably jeopardize its water supplies in the times of drought or conflict.xv

India has been unlawfully building dams and hydropower projects on the western rivers and their tributaries. In fact, it has constructed over a dozen dams in Indian Occupied Kashmir on Chenab, Indus and Jhelum rivers, thereby waging a silent war against Pakistan by violating the Indus Waters Treaty. India is trying to use water as a weapon of war, which could potentially cause hunger, death and destruction in Pakistan.xvi In the recent past, Indian policymakers unabashedly threatened to revoke the treaty and run Pakistan dry. For instance, in the aftermath of the Uri attack in 2016, India’s Ministry of External Affairs Spokesman Vikas Swarup remarked about the Indus Water Treaty, “There are differences on the treaty. For any such treaty to work, it is important there must be mutual trust and cooperation. It can’t be a one-sided affair.”xvii Many observers deemed it as a veiled threat to Pakistan that India may revoke the Treaty. Ultimately, New Delhi did not abrogate, but suspended meetings between the Indus Water Commissioners of the two countries. This demonstrates that Pakistan’s concerns stemming from the “water terrorism” being perpetuated by India are real and vital.

Way Forward

It is important that both the countries work together for peace, mutual gains and shared prosperity. In this context, resumption of talks is a prerequisite for working together and advancing negotiations to achieve tangible results. Relations between Pakistan and India have been on a downward trajectory after the Pulwama attack, but the two countries must realize that dialogue is the only way forward. Also, the Indian government must realize that water negotiations could provide the much-needed thaw in relations that could pave the way for opening up of communication channels. This means that meaningful dialogue over the water disputes could create a positive domino effect, translating into Pakistan-India engagement potentially paving the way for resolution of all outstanding issues.

Furthermore, a multilateral regional organization such as SAARC could be utilised to diffuse bilateral tensions and forge cooperation in the area of water management. South Asia is blighted by water scarcity, water pollution and flooding, which have added to tensions in the region. While in the previous SAARC summits member countries have discussed several issues of mutual concern, water management remains a neglected subject. Water disputes in South Asia are interconnected; therefore, a collective solution for resolving these conflicts is needed.

The need for a comprehensive water dialogue between Pakistan and India dovetails with the desire to metamorphose the conflictual relationship between the two countries into constructive engagement. In this regard, the media as well as the civil society can play a pivotal role in creating mutual trust between Islamabad and New Delhi, thereby leading towards larger peace building initiatives. Taking into consideration that India and Pakistan are arch-rivals, having fought three border wars, and the hostile posture of the Modi government towards Pakistan, any suggestion for peace and cooperation is likely to be met by some degree of scepticism. However, it would be in the best interest of both states to transform the zero-sum-mentality underpinning their ties into the one based on engagement and dialogue.

Furthermore, it is also pertinent to mention the role of US in the water conflict between India and Pakistan. The close strategic ties between India and the US have exacerbated the India-Pakistan water dispute. During the Cold War era, India remained willing to respect the Indus Waters Treaty and amenable to address Pakistan’s concerns. A case in point is Salal Dam, when Pakistan raised objections in the 1970s over its design, India modified it. Another example is of Wullar Barrage/ Tulbul Navigation project, when Pakistan objected to its design, India halted construction activity. However, development of close Indo-US strategic partnership has emboldened New Delhi, which has started violating the IWT with impunity. It is in this context that India is pursuing a number of new projects in stark violation of IWT, such as Ratle, Lower Kalnai and Pakal Dul.xviii The US should play the role of a responsible power and deter India from playing the role of a regional bully, antagonizing its neighboring countries.

Lastly, the demand for water is going to increase in Pakistan in the future with its rising population and expanding economic needs – a manifestation of this lies in the severe shortage of water in many parts of the country. Hence, Pakistan also needs to look inwards and take practical and urgent steps to improve its existing water infrastructure. Doing so would have the added advantage of putting Pakistan in a better position to voice its concerns regarding India’s hydroelectric power projects that are jeopardizing its water supplies.